Through watercolours, poetry, and the quiet strength of collaboration, Ripley Fletcher and Stefania Illieva build a world where softness is strength and history speaks back.

neun Magazine had the opportunity to interview Ripley Fletcher (they/them) and Stefania Illieva (she/her), two recent Central Saint Martins graduates, who are paving their way organically through the competitive London art scene. These two ‘quirky brunettes’, as they like to describe themselves, are two undaunted figures that share a beautiful, collaborative friendship they used to bring people together through Ripley’s folk-inspired retellings of queer history and their personal journey through poetry in an exhibition titled ‘Harbour’.

Let yourselves, as I was, be swept into Ripley’s art and their fantastical world, curated through Stefania’s adoration and profound empathy for her dear friend. In their own words, I am delighted to introduce you to them.

On a rainy Sunday afternoon, we meet at Ripley and Stefania’s apartment, which is adorned with Ripley’s paintings and sculptures. We gather in their living room and talk everything art and friendship.

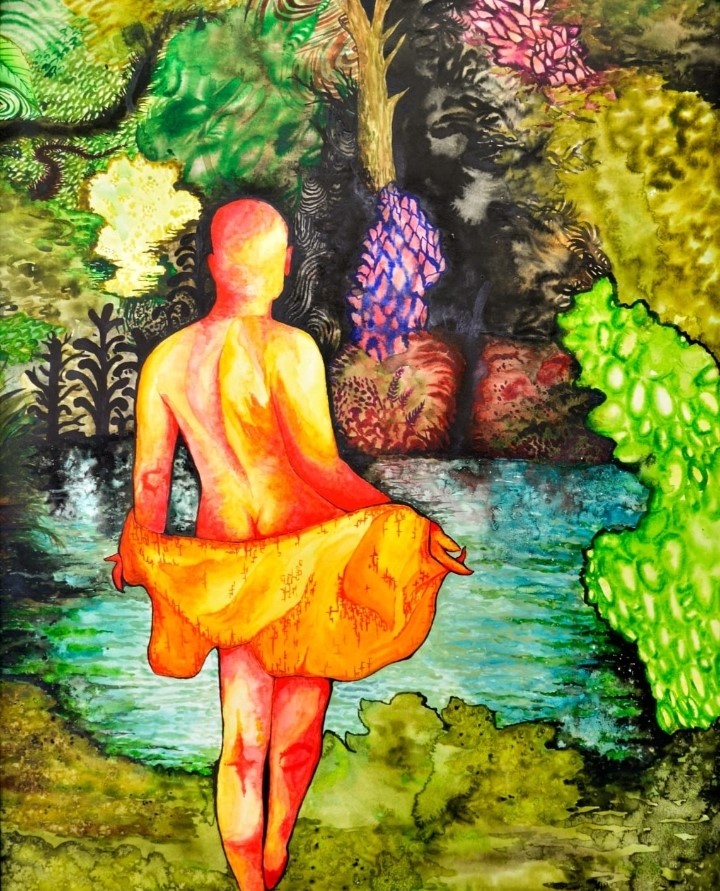

Ripley: I am a painter and a writer based in Hackney and East London, [originally] from Northumberland. My practice is predominantly large scale watercolour paintings that are based on folklore and queer anthropology research, which is the performance basis of my writing. I write research texts and poetry, and my work is informed by inquiry based studies of folk culture, particularly looking at genderqueer and homoerotic characters and narratives from ancient stories.

What about folklore attracts you?

Ripley: Since I was a little kid, I was obsessed with drawing what I would describe as ‘femme monsters’ – female or feminine presenting creatures from mythology, like mermaids, sirens, harpies, girl dragons or suspiciously shaped dragons. As a little gay kid, I was obsessed with drawing these feminised creatures. I was quite quiet when I was kid, and I just used to draw these creatures. I had books and books, (I’ve still kept a lot of them) that are filled with these weird, twisted drawings.

A lot of them are based on Greek or Gaelic folklore. It evolved into what I researched as an adult within my practice. One of the main reasons I focus on this subject matter is that I really enjoy delving into the history of my community. A theme that comes up a lot about people who are genderqueer or transgender, or the gay community in general, is that it’s something new, of younger people. I really enjoy looking into the ancient history of queer people.

People just don’t care to look at it, even though it’s something that is fairly well documented across different cultures and different parts of the world. Queer people aren’t a new thing. I like looking at and making artwork to inform people that there is this really rich culture and backlog of interesting stories and characters that have been missed or rewritten.

Are there any figures specifically that you’d like people to know more about?

Ripley: I’ve made a series of six watercolour paintings that are about this one story, and it’s the story of the hermaphrodite. The story of a character called Hermaphroditus, from the ancient Greek Cypriot story, who is the child of the gods Hermes and Aphrodite, that’s where we get the modern word ‘hermaphrodite’ from. This character is a God who is both male and female, and their origin story serves as an origin myth, an etiological tale, which is a story that seeks to explain the way something that is naturally occurring comes to be. It serves as the ancient origin story for how people understood the presence of genderqueer people in the ancient world and in certain Greek islands, and how this God had a following.

The story goes that Hermaphorditus was born male and had their body combined, later in life, with the body of a female nymph, then the two emerged as one. The story has been retold a few times, considerably. In one of these retellings, the narrative follows the downfall of a male character at the hands of a woman, which is quite a common theme. The male character is punished with the attributes of a woman at the hands of an evil nymph character.

This metamorphosis was also the inspiration for some characters in A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Shakespeare, it’s a story that’s been woven into a lot of classical pieces of literature.

What have you brought with you from your childhood, or from where you’re from, into your storytelling?

Ripley: The main thing that springs to mind is that I brought forth this unconscious need for queer escapism from everyday life, which is something that I definitely did without realising.

What do you mean by ‘queer escapism’?

R: Immersing yourself within a self created world, using my art practice and these stories and my paintings and my pottery to remove myself from some aspects of the real world, which is something I certainly did without realising as a kid. Now, it reflects in an interesting way in my art practice.

How do you see it reflected?

Ripley: I would say my work is fantastical, it’s mythological, it’s imaginary, but it’s politically informed by my everyday life as a genderqueer person. There is the need to redecorate your truth through these things that don’t really exist –like folklore narratives–to help you to better manage and navigate your everyday real existence in the world, as someone who visibly exists outside of societal understanding.

We went on to talk about the perpetual importance of queer stories, their diversity and richness can serve as just as powerful a message as political protests, in Ripley’s words: ‘It’s important to highlight that queer stories can be whimsical and about celebration rather than a protest’.

I wanted to ask you about poetry now, when did you start writing it?

Ripley: Three years ago. I spent the last four years of my life living on a traveling canal boat in London and I started writing poetry based around living, off-grid and traveling around the UK and London. That’s when I started writing poems based on the bits of river where I was living, the wildlife and the nature that I was immersed in whilst living on a boat.

Do you see writing poetry as something that goes hand in hand with your painting? Or are they just separate things that have separate purposes?

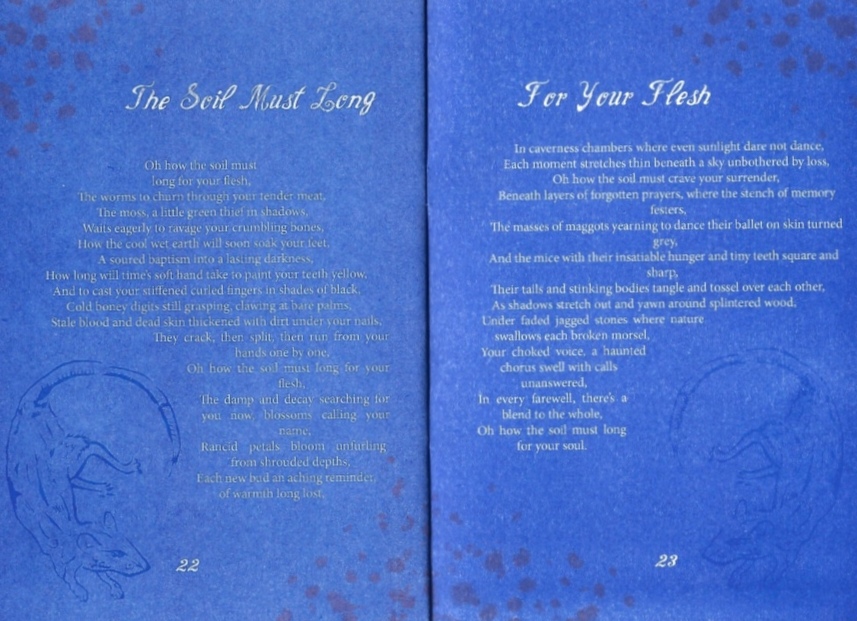

Ripley: They go hand in hand. I think they do that subconsciously because of the way that I work. I think my research writing, my poetry and my paintings all have the same feel to them. A lot of the poems are like, physically written into the paintings. The backgrounds are made of words, and the poems are actually inside all of the paintings. Almost all of my paintings have a poem that goes with them. Mostly, I do the poem first, and that develops into the painting.

From your poetry, there is a noticeable recurring presence of women or female figures in some way or another, going back to what you said earlier about these figures fascinating you, why do you think these female figures have such a hold on mythology in itself, but also on you?

Ripley: I have a fascination with these kinds of narratives. I think I write from their perspective in the poems. They just have a hold on me. It’s just inescapable. I think it’s somewhat more interesting sometimes to look at women who do not necessarily reflect what we think of as a woman. Maybe it’s an evil figure, but maybe it’s a woman who is physically not in the shape that we expect women to be. There is something really attractive about thinking of women in this sphere of darkness and fear, something we typically associate with men more.

It’s at this point of our interview that I asked Stefania to chime in and expand on her views of Ripley’s work as a curator and a long time friend of the artist.

Stefania: It’s very interesting to see all of these women’s presences in Ripley’s work. I think fundamentally, they’re really important to the way that Ripley has looked at the world a lot of their lifetime. Through being close friends, I know that the presence that the women in their family, specifically their grandma, holds to them, is really important.

And I think this alluring aspect that women bring, and the magical touch that they have to make the mundane life seem a bit more magical is part of this fascination. That’s why I love their artwork and their poetry so much, because it brings this familiarity as well. I also look at women like that, and I think without women, we wouldn’t have the sort of illusion or ability to look at the world with the magical realism that wouldn’t be present without women.

Do you think other people think that way?

Stefania: Certainly not. But I think that comes with the privilege of growing up with a woman that has really inspired you in your life, but [Ripley and I] were talking about how I think I’m more influenced by men in art, whilst Ripley is more influenced by women in art. I think it’s an interesting perspective because I don’t think people are able to recognise [what inspires them] most of the time.

But, when you’re a passionate, creative body, you’re always looking at what inspires you. And women, for me, are the centre of that creativity.

Let’s talk about the exhibition you two put together, how did that come about?

Ripley: The title of the exhibition is ‘harbour’. It’s the same title as the poetry anthology, and it’s my first solo show in London since graduating. It’s a watercolour painting exhibition, and it’s also going to be used as a book launch for my poetry anthology, which is a risograph print made in collaboration with PageMasters, a studio who supports my work in Lewisham in South East London.

The work looks at a couple of different stories, different narratives from folklore and from mythology within the paintings, and it’s also an exploration of my own personal journey over the last few years. I define myself as queer, I’m intersex and non-binary and the work looks at the origin of the way we perceive these people, and ways in which we can view them.

The work also explores my own emotional journey. I unpack a lot through the paintings. I place myself within a couple of stories in the exhibition, looking at my recent breakup and my emotional journey of self-realisation, since not being in a long term relationship. It’s an exploration of my own gender and sense of self, and how I see myself existing independently in the world.

How do you see yourself existing?

Ripley: Coming out of a long term committed relationship, a gay relationship (I’m non-binary but I was in a gay relationship), into having the subconscious freedom to view myself in a way. Since coming out of that, a lot of my work and my own emotional journey has been having the freedom to really express my agenda in a way that only has to work for me. I am my own priority. That’s something new for me and the work looks at the self-reflection and realisations around who I am and who I want to be, and maybe it’s how people perceive me.

It’s very liberating. I’m describing it in a very serious sounding way, but, this exhibition, it’s very fun, it’s light-hearted and it’s almost a romance of the sense of self. It feels authentic, very fulfilling and true.

Are there more questions that you’re looking to explore with your work? Are you ready to move on to other things?

Ripley: I feel like my work is taking a slight inquiry, documentary shift. It’s still paintings and pottery, but it’s developing more from bringing the stories from the ancient past into a sense of modern self, into doing more community based work within the underground queer community in London, finding my place and with my work within that scene, within those people.

Stefania, what role did you have in this exhibition?

Stefania: Me and Ripley have been working together and collaborating together for a while now, this is our third project. I think I’ve come from a place of privilege in terms of that I have known Ripley for a few years now, working with them, I have had access to the personal narrative that they’re trying to display, but in a bit more intimate way, perhaps. So, when they were creating this body of work, they asked me to come onboard. They have always had a knack for being able to involve the people that they love into the projects that they do, it’s something that I really admire about them. I was brought into this project as a friend, but then through it all, I’ve kind of always voiced and vocalised my appreciation for their work.

I think me and Ripley intersect, and our characters intertwine in that bit, even outside of our professional work. As serious as it is, and as emotional as all of this is. It’s a fun exploration, as well as something that we got to do, not only as collaborators, but as friends, that’s really important for me. Obviously, it makes the job of the curator a lot easier, because you already know the person.

To be honest, I was much like the audience would be, an observer and a very appreciative one at that. I wouldn’t say, gave them encouragement, because they’re confident within their work, but I gave them a sort of presence within their work. And then we came to the main part, putting the booklet and the anthology together. There’s a poem about me in there that I love, and it’s actually the first poem that anyone has written about me, ‘Our Lady of Song’. We sat endless nights on this settee that we’re sitting on right now doing the anthology. So, it’s really nice to officiate this creative partnership between me and Ripley, I hope we will go on for many years to come!

Both of us growing up in the north, we identify with this miserable aspect of being in the north. And we’ve always come together in these beautiful conversations about these stories that we listened to when we were kids, or these like presences that we observed in different films, music, literature, anything. I’ve always thought of these conversations as very special ones and ones that I can’t really have with other people. So I’m glad that, in a way, through these paintings and through these poems, people can get to know all of these beautiful aspects of the human experience. It’s nice that someone is able, like Ripley is, to narrate them in these beautiful forms. It’s such a magical thing to be able to sweep up all of these beautiful folk narratives and then twist them in a poetic way to intertwine within daily life.

Ripley, what would you like your audience to get from what you’re putting out there?

Ripley: I would like them to have been made aware of something that they didn’t know about before. So, I guess I want them to leave informed of some element of history, something new and exciting. I also want my exhibition and my work to really hammer home the human behind the gender queer community.

I want people to read and see my work, meet me and really view us as real. I want people to view us as interesting, valuable, and important people within society. I’m talking about genderqueer people and specifically trans people. I want people to view us not as statistics, not as something to be afraid of, or not as a political discussion topic but I want people to view us in an emotive way.

To view us as the beautiful, human, emotional and valuable bit of community that I see ourselves as. We are so varied and worthwhile knowing, I want people to go away from my work and myself wanting to support other members of my community. We’re currently in a time where the political tensions and violence towards queer people, towards gay people, specifically towards trans people is really on the rise. I want people to support us and shift the narrative.

Stefania: As a curator, you want the main message to be the one of the artist. I want to support and vocalise and make people aware of, continue to support and bring attention to the community. Selfishly, I think it’s nice to bring light on the fact that, it’s just the girls and the gays truly coming together to put on a show, and show unity and friendship?

I have been very privy to having such a personal connection with Ripley and being their curator. You know, we’ve all been through heartbreaks. We’ve all been through the feeling like maybe perhaps we don’t fit in, into the narrative that we occupy. And I think it’s nice to have shows like this, with artwork and poetry like this, to be able to make people feel united. That is something that I want people to feel. When they look at these paintings and read the poetry, I want them to feel like they’re engulfed in Ripley’s world, which is so magical. I want people to feel like they’re talking to Ripley and like they’re friends with Ripley, and then they can get to, sprinkle magic dust on the world and make it feel better.

Just celebrate the fact that times are sometimes shit, the world sometimes is shit, but we come together in a room, and we look at artwork and we read poetry together and we feel as one, we feel united, even just for a little while.

What’s next for you after this exhibition?

Ripley: I want to make more zines. I want to do more community based work, whether it’s, within nightlife or organising protests and pride events. I guess, the other thing is that I want to keep having fun with it. The thing that keeps making me produce work at the speed and volume that I do is that I have a lot of fun with it, and I don’t always take it super seriously. I just want to keep making weird stuff with the people that I love in my life, because that’s important. It’s a nice way to go through life and have stuff to show for it, have artifacts, and creations and things I live. I also want to work more collaboratively. I’ve recently started doing event planning for art and culture events, putting workshops together for a large event space in London. It’s something I want to delve into and have fun with and find my place within.

Stefania: I would love to work with Ripley till my last breath! With any sort of collaboration, that they want to invite me on. I also just feel like it would be lovely to continue in this kind of stride of portraying every single individual’s own little worlds. Bringing the community together, bringing the people that we love together, that is kind of like the main stride that I also look at. And, developing as a person, being in my 20s, moving to London to do all of these things, I’m excited to see what my creative journey brings on. As a curator, being able to initiate more shows, more exhibitions and work on my zine publications, following my own practice as well as being able to collaborate with people I think would be lovely, but from all sorts of different disciplines.

We concluded the interview with a rose-infused tea and a beautiful dinner where we discussed how we would live in our favourite time in history, creating alternate realities over a red tablecloth and where Stefania’s words about Ripley’s ability to bring people into their fantastical world came to life before my eyes.