Corinne Day’s unseen photographs reveal a haunting truth: girlhood was once private, slow, and sacred—before the world demanded it to perform.

Virgin Suicides by Sofia Coppola lives in the veiled light of memory—a film about adolescence, coming of age. It’s not about women, it’s about young girls on the threshold of womanhood, set against the backdrop of mid-1970s Grosse Pointe, Michigan. What I remember most about the film is the soft lighting—the girls are always in some hazy light, giving the impression that they are unapproachable, unearthly creatures, almost, existing in a dreamlike state. At least, that’s how the boys who live near them perceive them, as beautiful goddesses belonging to an unattainable stellar dimension.

I look at the Lisbon sisters and I think they’re like nymphs. Camille Corot’s La Danse des Nymphes in the Musée d’Orsay comes to mind—that very beautiful, whimsical, romantic, quite mystical feeling. You sense it with the early shot of Cecilia lying in the tree, so very much part of nature, organic. She becomes one with the beauty of the natural world, which brings me again to the idea that they’re ethereal, placed in this very suspended context.

Now, 25 years later, Corinne Day’s photographs emerge in Important Flowers as archaeological evidence of this lost world. As Coppola herself recalls in her foreword to this collection, she first encountered Day’s work in The Face magazine—”Fresh faced Kate Moss, with no make-up as a kid on the beach. Her photos didn’t look like the glossy 80’s fashion images I had grown up with: Tall girls with shoulder pads, bright lights, make-up and big hair. I could relate to these undone, slight girls and loved seeing the in-between moments, the photos that would usually be left out of the edit. Moments that felt real, not posed, with a relaxed naturalness about them that I hadn’t seen before in fashion photography. You felt like you were there with them and knew these girls, or wanted to.”

When Coppola began production on her first film in 1999, she knew she wanted Day on set. “Her gentle way was easy and relatable and began our friendship,” Coppola writes. Day came with her small camera to their Toronto set that summer, capturing what we now see – photographs that are completely voyeuristic, trying to grapple onto a kind of lost innocence. Those sun-flared shots feel like memories dissolving even as they’re being made. There’s something about how the light bleaches out parts of the frame, as if these moments are already half-ghost, half-dream. It’s a homage to an era, and the photos are nostalgic, deeply sad, because she immortalises these beautiful young girls in bloom.

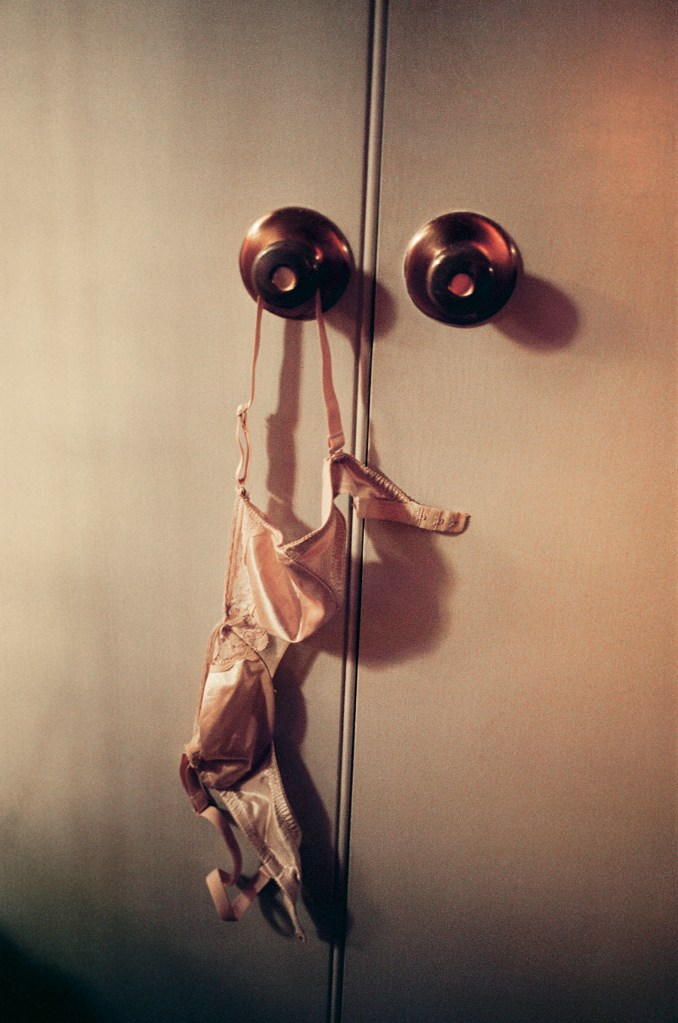

On the threshold of womanhood, there is this innate sexual awakening that you see manifested in Lux—this need, this surrender when you’re aching to explore first love, breaking away from childhood. Day captures this duality perfectly: You have that sexual tilt with the photograph of the pink bra hanging loosely from a wardrobe, this transformative physical beauty. Yet, at the same time, you have them sitting and eating, these very candid shots—childlike, fun-filled, innocent behaviour completely untainted by the adult world.

The photograph of the shoes with the long dresses before they’re going off to prom is subtly sensual. There was a time, before the 20th century, when for a woman to show her ankles was something very provocative, almost inviting. I find that shot interestingly appealing—the feet are played with, not completely standing, one is turned up. These here are visual metaphors of a lost era, bygone times.

The photograph of the three sisters together feels like a direct visual echo of their shared fate, but transformed into something almost Pre-Raphaelite, like John Everett Millais’ Ophelia multiplied, but here, they are alive, waiting. The hearse photograph, this everyday suburban detail, becomes weighted with prophecy once you know the film’s trajectory. Day captures the death that already haunts suburbia’s immaculate lawns.

Within the walls of their home, there is this stifled, oppressive atmosphere; they’re all chained, held back emotionally, physically, under the weighted protection of the parents. There’s a wonderful sense of juxtaposed naivety and this reckless, bold behaviour that comes with growing up, breaking the rules. I think that’s what Coppola does so well—this angel-like maiden appeal that she evokes throughout the whole film, to then bring the audience crashing down to these very real, raw shots of their suicides at the end, with the voiceovers of these young boys who are their witnesses. In both death and life, they are the transfixed voyeurs of these young girls.

Day immortalises these wonderful fun moments that cannot be repeated, whether they’re on or off set. It’s also a reminder that nothing is forever and that we live in worlds of constant change. The human condition is inherently the same regardless of which century we live in, what times we are in. We all want to love, to exist, to feel alive, to be held by another. This is constant in all of us, regardless of elapsed years or generations.

I believe that Coppola is leaning towards the bare, naked essence of the human condition whose tendency is to seek out individual expression and freedom. We’re not meant to feel chained within the parameters of family protection. We need to be able to find our voice and to speak, and this begs to be respected and loved by our own, by the ones whom we love, without constraint in a very selfless, trusting environment.

Is this film, with its amazing archive just released after 25 years, applicable to today? I am inclined to say that it isn’t a complete mirror, however there are elements that are invariably relevant because it has to do with human nature—we are all vibrant beings, growing up, experiencing.

Today, there is great parental insecurity—a trembling uncertainty born of our transparent age. Social media has dissolved the veils between public and private; everything is illuminated, exposed. There’s a vanishing of protection, of self, of the blessed anonymity that once sheltered adolescence. We are all watched now, all known. Young people are thrust forward, asked to perform their lives before they’ve learned to live them. There isn’t a sense of a childhood state now, which is what Coppola really reaches and delves into in her film.

Day’s photographs are evidence of a time when adolescence was still a distinct life stage, not the compressed, surveilled experience it’s become. The girls in these photos have privacy, boredom, time to dream—luxuries now. In our current moment, the stages of growth blur into one another. The beauty of innocence has developed cracks, fissures through which childhood seeps away too soon. We no longer know where one phase ends and another begins; it’s all morphed into this relentless forward motion.

This is why Virgin Suicides endures as such powerful cinematic work—it reminds us that we deeply want to live. We want to be the conductors of our lives, to write our own stories. We seek that freedom, and the film captures this yearning exquisitely. It’s heavenly and tragic all at once, pulsing with the raw ache of being alive.

The film devastates precisely because of its beauty, moves us through its tragedy. Its truth, so essential, so painfully human—is what makes both the film and these newly revealed photographs so profound. Through Day’s lens and Coppola’s vision, we see ourselves reflected: That eternal struggle between protection and freedom, innocence and experience, the desire to be held and the need to fly. These images, hidden for a quarter of a century, return to us now as both memorial and reflection—showing us not just who those girls were, but who we all are in our most vulnerable moments of transition.

Twenty-five years on, Important Flowers, has given us something precious. In loving memory of Corinne Day, 1962-2010, whose eye for the “in-between moments”, captured what we’re all searching for: to be seen, truly seen, in all our undone naturalness. Perhaps that’s what moves us most about these photographs—they hold up a mirror to our own longing, our own brief bloom, our own inevitable fading. They remind us that we were all once, simply, waiting to become.