The poet stands on the precipice of greatness, transforming shame into solidarity and wounds into words that heal millions

At 30, Caitlin O’Ryan sits on the edge of something monumental, though she herself might not fully grasp the magnitude of what’s unfolding. In a cramped Zoom frame, speaking from her London flat, she embodies a paradox that defines her generation: utterly vulnerable yet impossibly strong, completely undone yet profoundly purposeful. What I’m witnessing isn’t just a poet or activist, but the emergence of a universal voice that will speak for millions who have been taught to swallow their shame in silence.

There’s something almost alchemical about what O’Ryan has accomplished in her twenties – the deliberate transformation of psychological wreckage into creative gold. Where others might see damage, she has built an empire of empathy. The imposter syndrome that once paralysed her at drama school has become the very vulnerability that allows millions to see themselves in her work. The shame that made her feel worthless has been weaponised into a movement that tells women they are enough, exactly as they are.

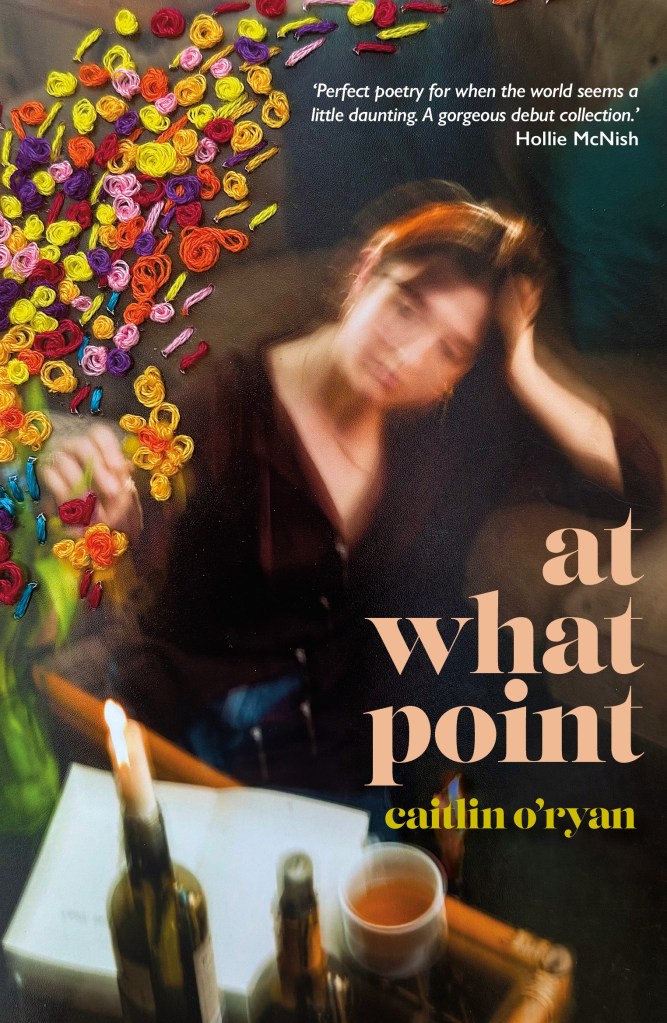

This is not potential we’re discussing – it’s kinetic energy. Her poem “At What Point” didn’t just go viral; it became a clarion call that reached 16 million people because it articulated something universal that had been surviving in silence.

What strikes me most profoundly is that O’Ryan stands at the threshold of greatness precisely because she refuses to pretend she has arrived. The actress who spent seven years on the renowned series Outlander, has found her truest voice not in someone else’s words, but in her own. In an age of performed perfection, she has made her undoing her masterpiece. As she steps into her thirties, armed with a debut poetry collection and an unshakeable commitment to truth-telling, we are witnessing the birth of a voice that will define this moment in women’s history – a voice that dares to speak all that we have been ashamed to feel, think, and be.

Strip away the viral videos, the Glastonbury performances, the 16 million views. Here, in this intimate space between question and answer, is Caitlin O’Ryan as she truly is – not performing, but simply being.

“I think for me, it is a lived experience. I write about things that frustrate me and make me angry. Writing for me is a form of therapy, it’s a form of working through my own discomfort with things.”

O’Ryan doesn’t write from inspiration; she writes from irritation, from the grinding reality of being a woman in a world that hasn’t made space for her truth. The poems that have moved millions began as private excavations, her way of processing overwhelming emotions by distilling them into something she could understand and eventually share.

“When I was like 20, I was this insane people pleaser. I had so much shame from being a woman… I just felt scared all the time, whether it was that people weren’t going to like me, that I wasn’t enough.”

This is where the foundation was laid – not of confidence, but of radical self-acceptance through vulnerability. Drama school became her crucible, a place where she recognised the institutional differences in how women and men were treated, where she felt like a fake for three years, waiting for someone to realise she didn’t belong.

“For three years I felt throughout drama school, that it was a fluke that I’d got in there and I was waiting for someone to realise that I shouldn’t be there, you know? I just felt… this real disconnection from my own voice as well.”

The irony is exquisite – a woman who now commands the attention of millions once felt voiceless in the very institution meant to teach her to speak. Drama school didn’t just fail to nurture her; it nearly silenced her entirely. She left with “really low self-confidence,” believing auditions were “my idea of hell.” The traditional path had broken her, so she forged a new one.

“I feel like my power is my vulnerability and my sensitivity. I’ve always been told that I’m overly sensitive… It’s actually your superpower.”

Here is the revolution distilled into a single sentence. In a world that teaches women to apologise for feeling too much, O’Ryan has weaponised her sensitivity. She discovered that the very traits society labeled as weaknesses – her emotional intensity, her inability to pretend everything was fine – were precisely what the world needed to hear.

“I literally wrote that for me and when I first performed it, it was the most terrified I’ve ever been because it was the rawest thing I’ve written and it was essentially standing up in a room full of people and saying this thing happened to me.”

She’s speaking here about her “consent” poem, ‘Yes is Complex’, written in her bedroom about the “grey line” where bodies say no while voices stay silent. The terror she describes is palpable – imagine standing before strangers and offering your most private wounds as public art. Yet something profound happened in that vulnerability.

“People thank me for doing my poetry and I’m like no, no, no, thank you. You don’t understand how much it gives me… the therapy for me is that, okay, I’ve said this thing, I’ve survived and I’m not alone in this feeling. No one is thinking less of me right now.”

This is the alchemy at work – personal pain transformed into collective healing. O’Ryan writes from her own fractures, then watches as thousands recognise their own reflections in her words. Her bedroom confessions become battle cries for women who have never had language for their experiences.

“You write something in your bedroom for yourself and then you go and perform it. The first time that you perform it, it’s yours and it’s very raw and it’s very vulnerable. Then what I find is the more that I perform it, the more it becomes for everyone else and the more it’s theirs.”

Watch the transformation unfold in real time – O’Ryan describes the precise moment when private pain becomes public power. Her bedroom scribblings, meant only to help her process her own confusion, become anthems for the masses. This isn’t accidental; it’s the natural result of someone brave enough to speak what others can only whisper.

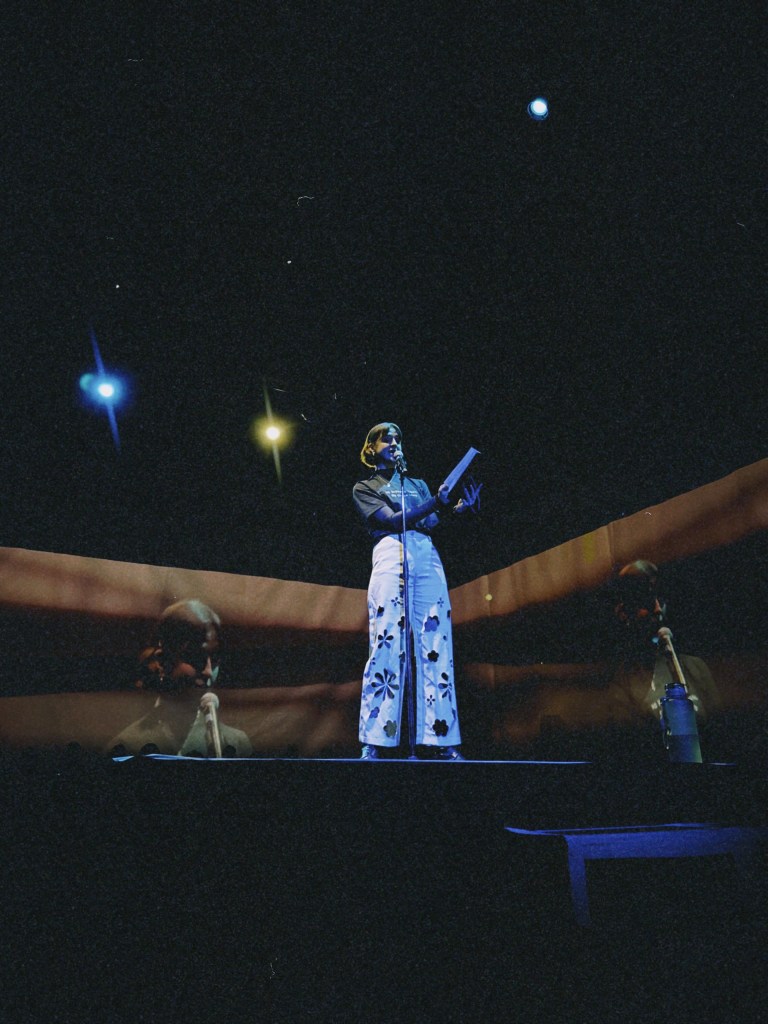

The process terrifies her every time. She admits to standing in pubs at open mics, “shaking with a bit of paper” while old men wondered what she was doing there. Yet those same skeptics would be moved by the end, drawn in by “the humanity in it, the vulnerability in it.” This is her genius – she doesn’t demand attention; she earns it through radical honesty.

“My best friend Norah used to come to all of the first open mics with me. I would get really upset if I messed up a line or if I slipped up, I’d be berating myself for it and she’d say to me, ‘This is different from acting – it doesn’t have to be perfect. You’re doing this purely because you love it, for what it gives you personally.’”

Here lies the secret to her power – she performs not for external validation but for internal fulfilment. While the world offers her platforms and followers, O’Ryan remains tethered to something deeper: the healing that happens when truth is spoken aloud. She describes it as “the most nourishing thing in the world,” this act of sharing and listening within the poetry community.

“I love poetry because it allows me to exist at the height of my intelligence. You know, acting, you’re grateful if you get given a role that is nuanced and has depth and aligns with your politics… What poetry does is I get to decide what that is for myself.”

This isn’t just career preference; it’s creative liberation. After years of embodying other people’s words, poetry allows her complete intellectual and emotional autonomy. The transformation required healing first; she admits to needing extensive therapy to work through personal experiences, ensuring she could write from a place of processing rather than raw wound. “What I recognised then was, oh, talking does help.” This therapeutic work allowed her to maintain healthy boundaries around what she chooses to share – her poetry comes from reflection, not unresolved anguish.

Then came the earthquake. After eight seasons, Outlander’s final season wrapped – O’Ryan had spent five of those seasons, her entire twenties, embodying someone else’s story. “I got Outlander when I was 22 and I’m 30 on Saturday. So it’s really been my entire 20s,” she reflects. The timing felt cosmically significant: as one decade ended and another began, her identity crisis became creative rebirth. “At What Point” exploded across the internet, stunning even her.

The poem, written in her Walthamstow bedroom after Sarah Everard’s murder – a tragedy that occurred very close to where she used to live in Streatham with three flatmates – captured immediate, visceral fear rather than abstract theorising about women’s safety. What began as one woman’s terror transmuted into verse became a rallying cry for millions who recognised their own midnight anxieties in her words.

“I was in New York. Outlander had just finished. I was like, who am I, where am I, what am I going to do? I don’t know who I am without this job.”

Yet while she questioned her identity, her art was about to provide the answer.

“Danny, who runs SpitNights, sent me the video and he was like, here it is. I watched it and genuinely I was like, I hate how I look in that. I’m not going to post that. I go to New York, I land. Danny’s posted it by the time that I land and he’s like, you need to get TikTok. It started going viral.”

The universe, it seems, had other plans. While O’Ryan wrestled with self-doubt, the poem found its own wings. She describes the surreal experience of walking through New York while her words spread across the globe, reaching women who had been waiting their entire lives for someone to articulate their fears about simply existing in public spaces.

“What happened is that overall it was women sharing their stories in the comments and I was walking around New York and I kind of had to take myself away and just sat and read them and cried.”

The cost of such visibility weighs heavily. O’Ryan speaks candidly about the price of being a woman who refuses to stay quiet about uncomfortable truths.

“There is an element of me having to decide what I am and am not willing to share and talk about. I definitely feel the sensation that I intimidate people sometimes, which is insane to me.”

She watches men shift uncomfortably at Sofar Sounds events, designed for intimate acoustic performances, when her political poetry disrupts their comfortable evening out. The statistics from her viral moment tell their own story – 95% of her new followers were women. Men, it seems, haven’t found a comfortable place for themselves in her revolution, or haven’t been shown it in their algorithm – a separate problem entirely.

“Every time that I perform, once I come off stage, it’s like I’ve left a piece of myself there. People want to come up to you and get back to the lightness, but I’m feeling quite raw sometimes.”

Yet she continues, driven by something deeper than career ambition. Her political voice emerged not from calculation but from moral necessity. She speaks about Palestine with the same unflinching honesty she brings to women’s experiences, knowing it may limit certain professional opportunities.

“I’m very aware that using that platform is likely going to upset some people and potentially will lead to me not getting certain jobs because of that. I just can’t imagine not doing that.”

Here lies the core of O’Ryan’s integrity – she would rather sacrifice professional advancement than compromise her values. This isn’t performative activism; it’s an extension of the same sensitivity that made her poetry possible. She describes growing up as “a very sensitive child with a hyperactive imagination,” sitting in history class learning about World War II and thinking, “if I was there, I hope I would have done something.””

“This is the time, isn’t it? Sharing something on your platform is the least that anyone can be doing, right? It costs the least in a way. It’s just a very visual form of doing it.”

The child who imagined herself speaking out against historical injustice has become the woman who refuses to stay silent about contemporary ones. She recognises her platform as both privilege and responsibility, wielding it with the same careful consideration she brings to her poetry.

This commitment to authenticity shaped her debut collection’s curation process. Choosing which poems to immortalise in print became an exercise in vulnerability management.

“I knew that I was going to title the book ‘At What Point’ just because it felt opportunistic to go off the viral poem. I think what my writing is, is asking questions. It’s asking questions and it’s to provoke thoughts in other people.”

O’Ryan understands that her power lies not in providing answers but in articulating the questions that haunt us all. She acknowledges the limitations of her perspective – her Western lens, her specific experiences – while refusing to let those limitations silence her entirely.

“I can only write from my point of view and therefore, that’s why it’s so important to stay so in touch with integrity because the moment that you start trying to tick every box, to cover yourself, then I think that’s why you slip up.”

This wisdom reveals the sophistication beneath her apparent spontaneity. O’Ryan has learned that authenticity requires boundaries, that speaking your truth means resisting the pressure to speak everyone’s truth. She writes what she knows, feels what she experiences, then trusts her specificity to unlock universal recognition.

The apparent contradiction between her activism and her “don’t have your shit together” philosophy resolves into perfect clarity when she explains her understanding of effective advocacy.

“I think activism is staying curious and it’s staying open to learning and to accepting that you don’t know everything… You can’t fix everything and you have to be okay with not knowing and you have to be solid within yourself that what you’re trying is true and from a good place.”

This is revolutionary thinking disguised as humble confession. O’Ryan has identified the fatal flaw in traditional activism – the pretence of certainty that ultimately undermines credibility. She offers instead a model of advocacy rooted in perpetual learning, comfortable with its own fallibility.

“As soon as you start advertising yourself as the morality on certain issues, there’s only one way to go if you fuck up because we’re all fallible and we’re all human. The power is in the vulnerability and the power is in the willingness to unlearn.”

Here she articulates what makes her approach so powerful – she leads with questions rather than declarations, with curiosity rather than conclusions. Her activism succeeds precisely because it acknowledges its own limitations, creating space for others to join the conversation rather than simply receive instruction.

“It’s only been in my 20s that I started to truly unpack how society has been set up to fail women. It’s only, you know, I hate to say it, but George Floyd’s death, where I truly interrogated my racial blindspots, that I wasn’t even aware of having.”

She charts her own evolution without shame, modelling the kind of growth she advocates for others. Each revelation – about sexism, racism, environmental destruction, global politics – becomes not a source of guilt but an opportunity for deeper understanding. This is activism as personal development, advocacy as continuous education.

As Outlander ends and her poetry career flourishes, O’Ryan stands at a threshold that few artists reach – the moment when personal healing and public impact converge into something larger than either could achieve alone. At 30, she possesses both the lived experience to write with authority and the self-awareness to recognise how much she still doesn’t know.

“The key to life, I think, is not having your shit together. It’s from all of the mistakes where you’ve learned and you’ve grown. Not having your shit together, is what makes the whole thing make sense.”

In this final observation, O’Ryan completes the revolution she began in her bedroom. She has transformed the very concept of failure into fuel for connection, turned uncertainty into a philosophy of growth, made vulnerability into a methodology for change. She stands before us not as someone who has figured it all out, but as someone brave enough to figure it out in public, inviting us all to join her in the beautiful, messy work of becoming.

This is Caitlin O’Ryan unearthed – not perfect, not finished, but profoundly powerful in her willingness to grow and share and question everything. She represents not just a voice for this moment, but a model for how we might all speak our truths with both courage and humility. In her undone state, she shows us completion. In her questions, she provides answers. In her vulnerability, she offers us strength.

The revolution isn’t coming. It’s here, speaking in the voice of a woman who dared to turn her wounds into words, her shame into solidarity, her uncertainty into the most certain thing of all – that we are not alone in feeling lost, and that, perhaps, being lost together, is exactly where we need to be.