Poet Zeina Azzam on “Write My Name” and testimony

Today marks the International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People — a day when the world is called to stand witness. Yet “Write My Name” refuses to be contained within the neat boundaries of designated remembrance. This poem breaks through the comfort of annual observance, demanding that we carry Palestinian children’s voices with us every day, not just when the calendar reminds us of humanity’s atrocities. It insists that solidarity is not a scheduled moment, but a daily reckoning with our own existence—a recognition that these are not anonymous names to be mourned once a year, but souls who deserve to know only joy, not the weight of their own mortality.

Stark and clear, palpable and translucent, were these few simple words that were enough to bear a most harrowing truth and the world unravelled in an instant.

“Some parents in Gaza have resorted to writing their children’s names on their legs to help identify them should either they or the children be killed.”

— CNN, 10/22/2023

“Write My Name” by Zeina Azzam

Write my name on my leg, Mama

Use the black permanent marker

With the ink that doesn’t bleed

If it gets wet, the one that doesn’t melt

If it’s exposed to heat

Write my name on my leg, Mama

Make the lines thick and clear

Add your special flourishes

So I can take comfort in seeing

My mama’s handwriting when I go to sleep

Write my name on my leg, Mama

And on the legs of my sisters and brothers

This way we will belong together

This way we will be known

As your children

Write my name on my leg, Mama

And please write your name

And Baba’s name on your legs, too

So we will be remembered

As a family

Write my name on my leg, Mama

Don’t add any numbers

Like when I was born or the address of our home

I don’t want the world to list me as a number

I have a name and I am not a number

Write my name on my leg, Mama

When the bomb hits our house

When the walls crush our skulls and bones

Our legs will tell our story, how

There was nowhere for us to run

Originally published in Vox Populi, October 30, 2023. Copyright © Zeina Azzam. Reproduced with permission.

I remember the moment I first encountered these words. The poem seized me, held me captive where art meets unbearable reality—there was something about the child’s words, the desperate simplicity, the way love and terror intertwined that left me breathless. This was an excavation of what it means to be human when humanity itself hangs in the balance.

I knew I had to reach out to Zeina—not as a professional strategy, but as an organic response to words that become bridges to the incomprehensible. Below is the reflection that emerged from my first reading, unguarded in its honesty, capturing my initial encounter with a poem which is so simple in its telling, so complete in its undoing.

“Some parents in Gaza have resorted to writing their children’s names on their legs to help identify them should either they or the children be killed.” I imagined Zeina’s experience to have been intensely similar to my own when she read how mothers were writing their child’s name on their legs: the horrifying reality of war, the fear of children, their bewildered gazes and their tear-filled eyes, the dirt on their faces and the emptiness in their stomachs.

“Write my name on my leg, Mama”—Here is a child grasping with tiny fingers not just the torn skirts of their mother, but the very possibility of being remembered. These six words tell of children covering their ears when they hear planes and raid sirens, and speak of the traces of bleak hope that they grapple with each day in a world that has not learnt from history.

“Make the lines thick and clear / and add your special flourishes”—while conflict governs our entrails, this child asks for mama’s handwriting. This child wants those familiar loops and curves that once meant safety, now inscribed as the last testament to the vitality and warmth that resided in these small bodies before the world deemed them expendable.

Zeina leads us into the geography where love is buried under the crushed remains of sunken homes and buildings, where a child’s simple request becomes a harrowing indictment of our collective failure to protect innocence.

Why the child? Zeina chooses the child to harness our sadness, our human disgrace, our innocence spurned and burned. Yet in this devastation, the child’s voice becomes a vessel for our own shattered innocence. We who watch from afar, we who scroll past images of small bodies under rubble, we who have learnt to metabolise horror as headlines whilst our hearts grow detached, distant, alienated.

I see in this child’s plea the stark, terrifying distress—the infinite turmoil of every war zone. Zeina weaponises our empathy against our numbness because she knows that a child asking “don’t add any numbers like when I was born / I don’t want the world to list me as a number / I have a name and I am not a number” will crack something open in us that news reports cannot reach.

Childhood becomes conscripted into bearing witness to what I call our human disgrace—that we exist in a world where mothers trace names onto fragile legs with permanent markers. Love must carve itself into skin because everything else that whispers “I existed, I was adored” dissolves under falling concrete and smoke.

The poem’s viral spread across continents reveals our collective hunger for undeniable truth. When pastors read “Write My Name” in Sunday services, when teachers print it on t-shirts, and when politicians sit in silence as these words fill their chambers, they surrender to a truth so elemental it bypasses politics, nationality, and all the careful distances we maintain from suffering.

Zeina’s work transcends because it strips away every comfortable lie we repeat to ourselves about war, every euphemism that blinds our thoughts in sleep. “Collateral damage” cannot survive in the same breath as “When the bomb hits our house / When the walls crush our skulls and bones / our legs will tell our story, how there was nowhere for us to run.” The clinical language of conflict dissolves when confronted with a child who is tragically aware, with heartbreaking precision, exactly what death will do to their small body.

Her global following exists because she has expressed an undeniable truth—we live in a world where innocence is not protected, where the human race hangs on the edge of its dehumanisation, consumed by exhaustive hatred. This is the reality we must accept: our collective humanity is measured by how we respond to such moments of unbearable clarity.

Zeina has excavated more than poetry from that news report—it is an exploration into the buried chambers of our shared humanity. In a world where love has been interred beneath the wreckage of stolen lives, where children must prepare for endings before they’ve learned beginnings, “Write My Name” becomes an act of resurrection.

The child’s voice carries forward what should be protected: the insistence that identity transcends destruction, that children should speak of a world that hasn’t been touched by pain. These are children who only know the soft cadence of unaltered laughter, whose feet tread the lightest of grounds. Children who seek the blue of the skies and find respite for their brief tears only within their mother’s embrace.

Perhaps this is why the poem haunts me so completely—because it forces us to confront our own tenuous hope, which we seek to nurture each day. I hear in this child’s voice our own desperate need to be known, to belong, to leave something of ourselves that cannot be erased. Zeina has given us a mirror in which we witness not just Gaza’s children, but the fragile architecture of our own humanity—always under threat, always requiring the deliberate act of being written into existence.

Ultimately, “Write My Name” reveals what I understand to be love’s refusal to disappear, even when the world conspires towards forgetting.”

When I shared this reflection with Zeina, what she entrusted to me in response became something neither of us expected. She opened her heart about her creative process, her struggles with privilege and guilt, and the profound weight of giving voice to Palestinian suffering. It became a testament to poetry’s most sacred power: to transform witness into universal clamour, to unite strangers around a child’s desperate plea for recognition.

Zeina’s first words carried the weight of those October nights when sleep became impossible. “Israel’s war on Gaza had been raging for just a few weeks at that point, and we were all reeling from the continuing carnage,” she told me. “It felt unstoppable and horrifying. I was often waking up in the middle of the night to read news on my phone, or unable to sleep because of the constant feelings of dread about the worsening situation in Gaza.”

The moment that changed everything came not through a screen, but through radio waves. “I actually heard this story on a radio newscast first. I closed my eyes and tried to imagine this shocking scene. It was so unbelievable that parents were writing names on their children’s arms and legs so they could be identified in death, which felt imminent for them and their children as bombs destroyed buildings, and ceilings and walls crashed over entire families.” Her voice carried the weight of that disbelief, the testament to “their utter despair in the face of such overwhelming firepower. I was aghast, incredulous, sad, scared.”

The poem emerged from that moment of overwhelming need to express the inexpressible. “I was at home and immediately started to think about writing a poem that could capture this anguish and powerlessness. It was an overwhelming moment, in a way; I felt like I had to express my shock and grief somehow.” The child’s words came to her as tears fell. “And it dawned on me rather quickly that I should write in the voice of a child. The words, ‘Write my name on my leg, Mama,’ came as I cried. To this day, I often choke up when I read this poem out loud.”

What struck me most was Zeina’s recognition of the power in that choice – to speak as the child rather than for the child. “Children should never have to endure violence and war, crushing fear, dismemberment and death all around, injury and amputations, the annihilation of homes and loved ones. I wanted this child’s voice to reach our conscience and our hearts. These were vibrant humans being killed so mercilessly; it seemed that the world viewed their lives as worthless and expendable.”

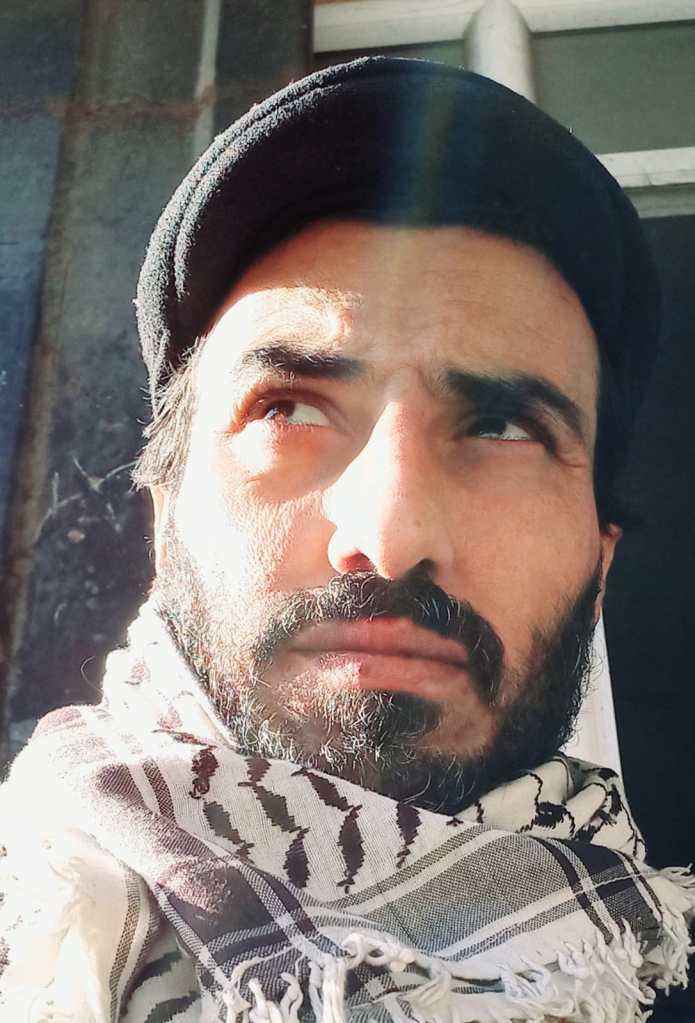

The line that pierces deepest – “I have a name and I am not a number” – carried personal significance beyond the immediate horror. Zeina volunteers with We Are Not Numbers (WANN), a writing programme for youth in Gaza that gives emerging writers the platform to “tell their stories and advocate for their human rights” beyond the news headlines that relegate them to being cold statistics. Her connection to Gaza runs through Ahmed, her last WANN mentee before this latest war. “I don’t have family in Gaza, so Ahmed became the thread that connected me. I have written about him and the stories he has told me about how he and his family have been suffering and coping with starvation and relentless bombings.”

But what emerged from her openness surprised even me. Zeina explained that although the heartrending stories from Gaza “became part of me as a Palestinian, and the voice of this child became part of my essence,” she began to question the very poem that had moved millions. “I also acknowledge that ‘Write My Name‘ is a persona poem that takes a child’s voice, and honestly, I have developed some misgivings about this type of poem.” Her honesty cut through any comfortable assumptions about artistic licence. “I know it is powerful to imagine and write about someone’s suffering in the midst of war, but I am now feeling like it’s not our place to do so—at least not to write in the first person.”

The weight of privilege pressed upon her words. “Who am I, a person who enjoys so much privilege from far away, to really understand the contours of their experience? I often feel so much guilt about living in such comfort and having food and shelter, while the people of Gaza are in the middle of a genocide.” The emotional conflict ran deeper still: “I am weighed down by intense cognitive dissonance because my US taxes are funding military aid to Israel, the country that is slaughtering my people.”

Yet even as she questioned her own authority to speak, Zeina defended the necessity of the work itself. “Just like all Palestinians everywhere, I also feel discounted and erased as a Palestinian in the United States. To be sure, there is tremendous solidarity all over the world for Palestine, and in the US too, but in the spaces of power and decision making, our voices are not welcome, and most often they are actually criminalised.”

Her response to this erasure was not silence, but a deeper commitment. “We need to continue to stand up to, and fight, this discrimination and erasure, building together on our grief and rage. Political and community organising is crucial, and it is all of our responsibility—both Palestinians and our allies.”

The poem itself, she revealed, was crafted with meticulous intention. “Everything about this poem was intentional: The progression, the same opening line and the number of lines in each stanza, the simple words, the usage of a child’s Arabic ‘Mama’ and ‘Baba,’ the words ‘When’ in the last stanza (instead of ‘If’), the sparse use of adjectives and punctuation.” She wanted something that would “carry the reader slowly and rhythmically to the end, which is heartbreaking in a quiet yet jarring way.”

What transcends all boundaries, she believes, is universal: “It’s the innocent cry of a child, suffering from within the brutality of war. It is unsettling yet pure. The welfare of children, and our love for them, transcends cultural boundaries, borders, and checkpoints.”

In the end, Zeina’s hopes for her poem return to where it was born—with the children themselves. “I hope this poem contributes a little to raising awareness of the immeasurable suffering of children in Gaza. Of course, everyone there is suffering, but hundreds of thousands of children are now scarred and emotionally traumatised forever. Over 20,000 have been killed (and this is likely an undercount) and thousands wounded, amputated, orphaned or left with no family at all. It will take them decades, if not multiple generations, to recover from this genocide.”

But beyond the statistics, beyond the political machinery of war, her vision reaches toward something more profound: “And through the words of this poem, I hope that we will envision these Palestinian children as beautiful human beings, feeling loved by their mothers and fathers, having a sense of belonging to family and home, and perceiving themselves as worthy individuals with happy and meaningful lives.”

And so we stand, in the square in Groningen, where 600 voices rose to carry a Palestinian child’s plea across the autumn air. Dutch composer Ep Wesseling, moved by powerlessness in the face of Gaza’s suffering, had found solace in creation—setting Zeina’s words to music so that an entire community could sing what one child had whispered. As I write these words, I am watching them -hundreds of people of all ages dressed in red, the Palestinian flag raised high above their voices. Shudders of emotional strain rush through me as I witness this moment. It grips me with such immense power, shreds my heart and yet – to see the crowd, the unity, the strength, the will to stand and sing – there is salvation, there is hope in humanity still.

In a world where love is buried beneath the debris, “Write My Name” stands as proof that some voices will not be silenced. The child’s plea has become our prayer, the poem our promise, and in that transformation lies the ever so fragile desire to dare to hope, and the knowledge that we must break these cycles, learn from history’s wounds, and choose to be humane – For love, however overused the word, remains the only saving thread that binds us together when everything else unravels.

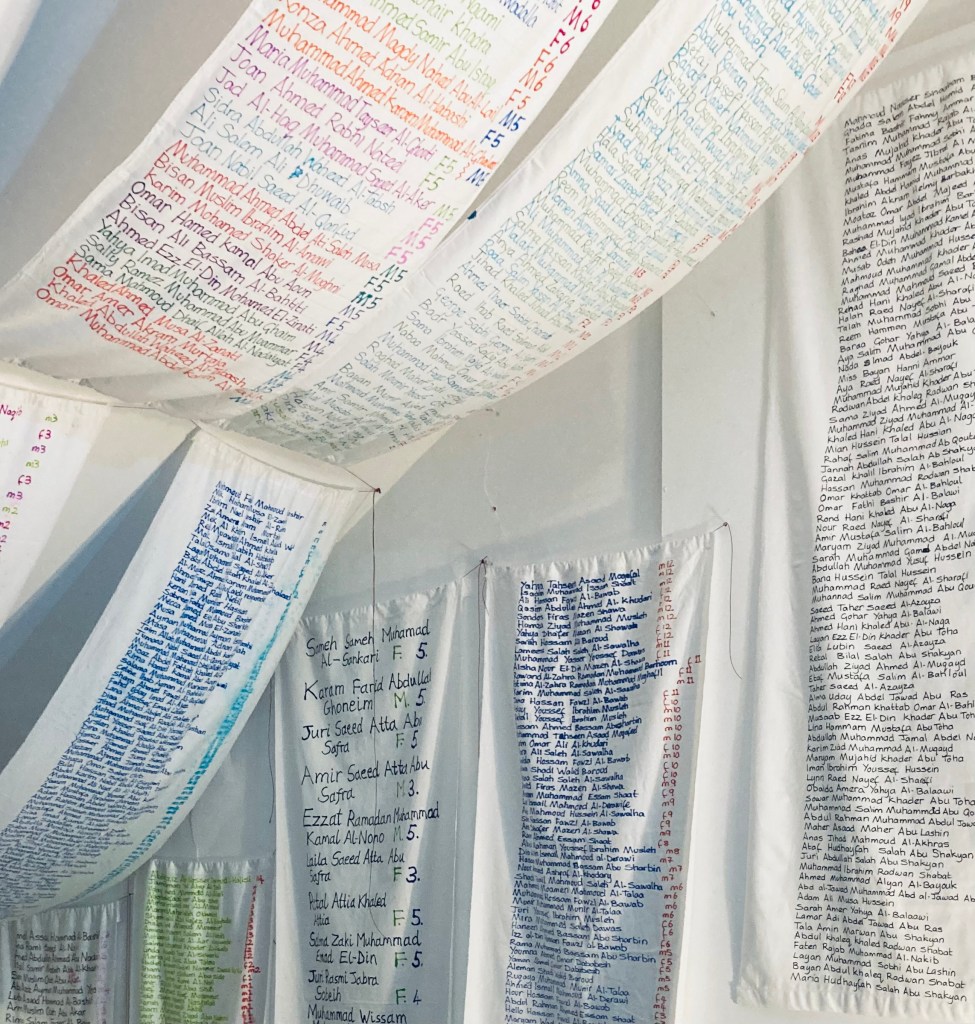

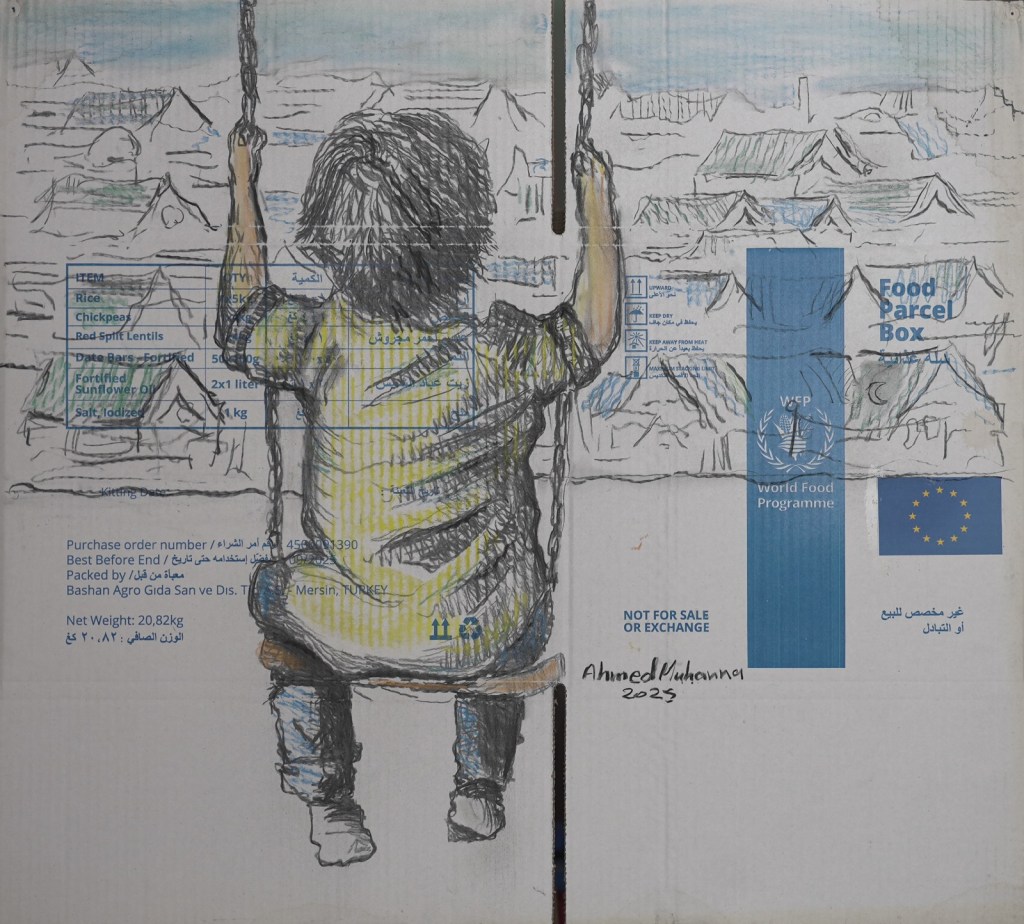

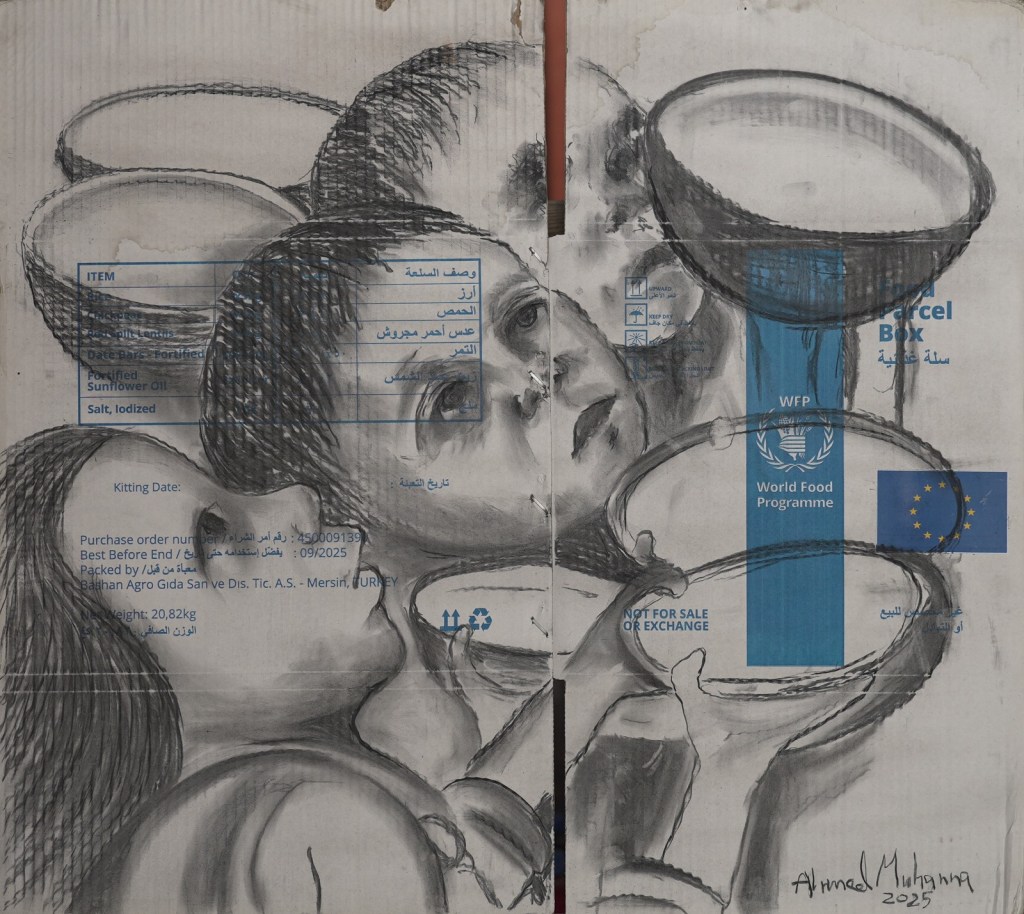

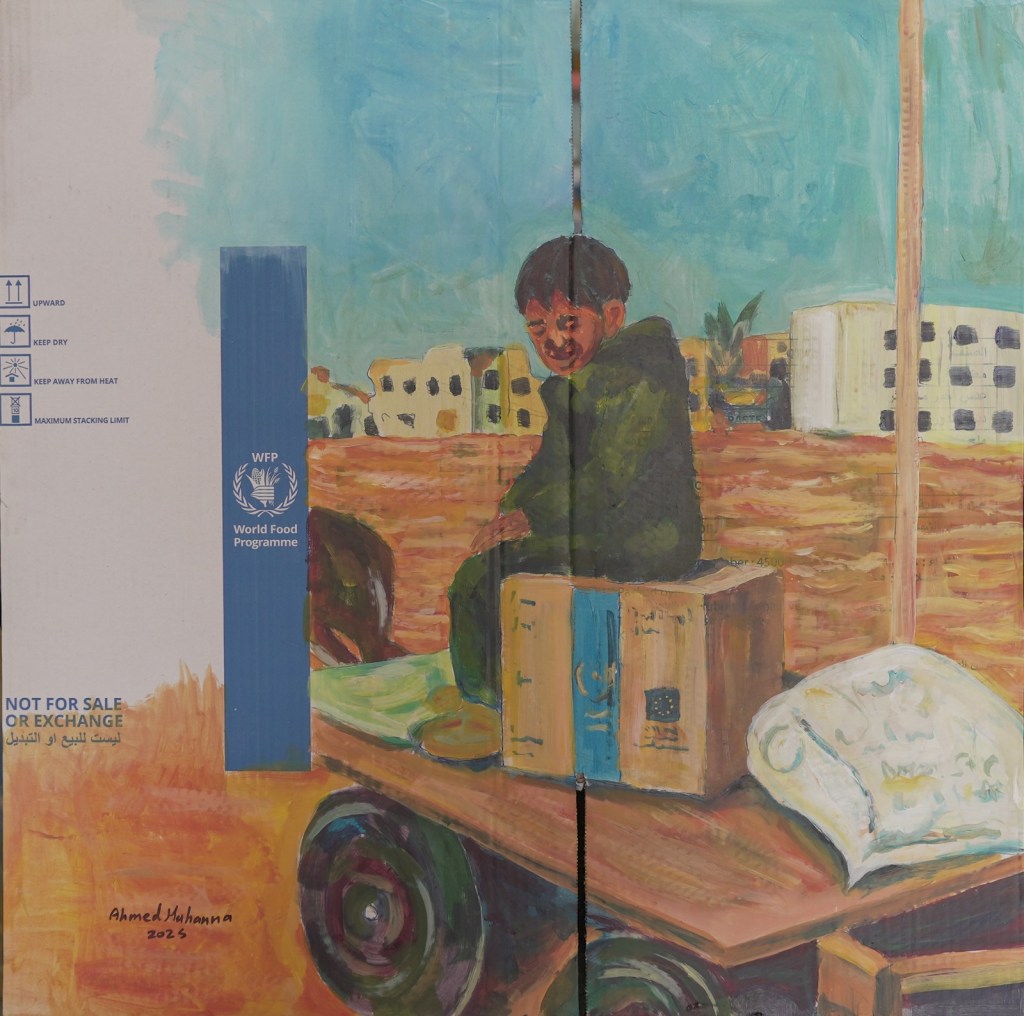

Visual Witness: Ahmed Muhanna’s Art of Survival

In my search for visual artists whose work could give weight and resonance to Zeina’s words, Ahmed Muhanna’s paintings emerged with startling clarity. Here was another creator who, like Zeina, had encountered an unbearable reality and found himself unable to turn away.

Just as Zeina could not disconnect from that radio report—those devastating words echoing in her mind until she felt compelled to write—Ahmed found himself surrounded by the cardboard remnants of survival. The WFP aid containers that sustained his community became impossible to ignore, each empty vessel a testament to hunger, exile, and the relentless machinery of need.

Where Zeina reached for words, Ahmed reached for his brush. Where she chose the child’s voice, he chose the most humble of surfaces—not the traditional stretched fabric of gallery walls, but these simple white containers, the most evident proof of devastation made manifest. In that choice lay a profound truth: instead of grand artistic statements, he painted directly onto the symbols of crisis itself.

Born in Gaza in 1984, Ahmed holds a Bachelor’s degree in Fine Arts and has participated in numerous exhibitions both locally and internationally. His most recent exhibition, “Gaza: Stories of Hope and Resilience,” was funded by the European Union and toured several European countries before concluding in Lille, France.

When art supplies became unavailable under siege, Ahmed began transforming those same aid containers—the cardboard vessels that had carried food to displaced families. He immortalised the children’s stories that needed to be told: small faces carrying water jugs, fathers holding lifeless bodies, the endless queues for survival.

“I try to convey my artistic message to the whole world,” Ahmed explains, “and this message transforms from an artistic one to a humanitarian one. Through my drawings, I try to raise essential questions: In Gaza, we are subjected to the most heinous crimes and genocide. What are you doing for people who live under genocide, death, hunger, and displacement?”

Ahmed stands with the poor, the marginalised, and the hungry. His creativity refuses to let the world look away. “The international community must look at us and care about us,” he insists. “We want to live in safety and peace—we need nothing more than that.”

From a single container painted in desperation came a global platform—a representation of Gaza’s tragedy that the world could finally see, could no longer deny or reduce to statistics. What Ahmed lived day in and day out, breath by breath, became testimony that the international community could hold in their hands.

Both Zeina and Ahmed understood something essential: from one word, from one brushstroke, emerges a movement. A philosophy. A mirror reflecting our shared humanity back to us. Sometimes it takes just one voice, one image, one refusal to remain silent, to create ripples that become relentless songs of hope, clamours for help, missions for human survival.

Ahmed’s creativity stands as proof that even in the face of adversity, imagination becomes a means of resourcefulness, and the canvas becomes a means of intercession. It is our innate endeavour to continue believing in light and purpose, which binds us to our humanity.