The vampire of pop speaks to us about fear, fandom, and the accidental alchemy of becoming

How the music, the mythos, and the fandom around him emerged not from intention, but from learning to lean into the parts of himself he once overlooked.

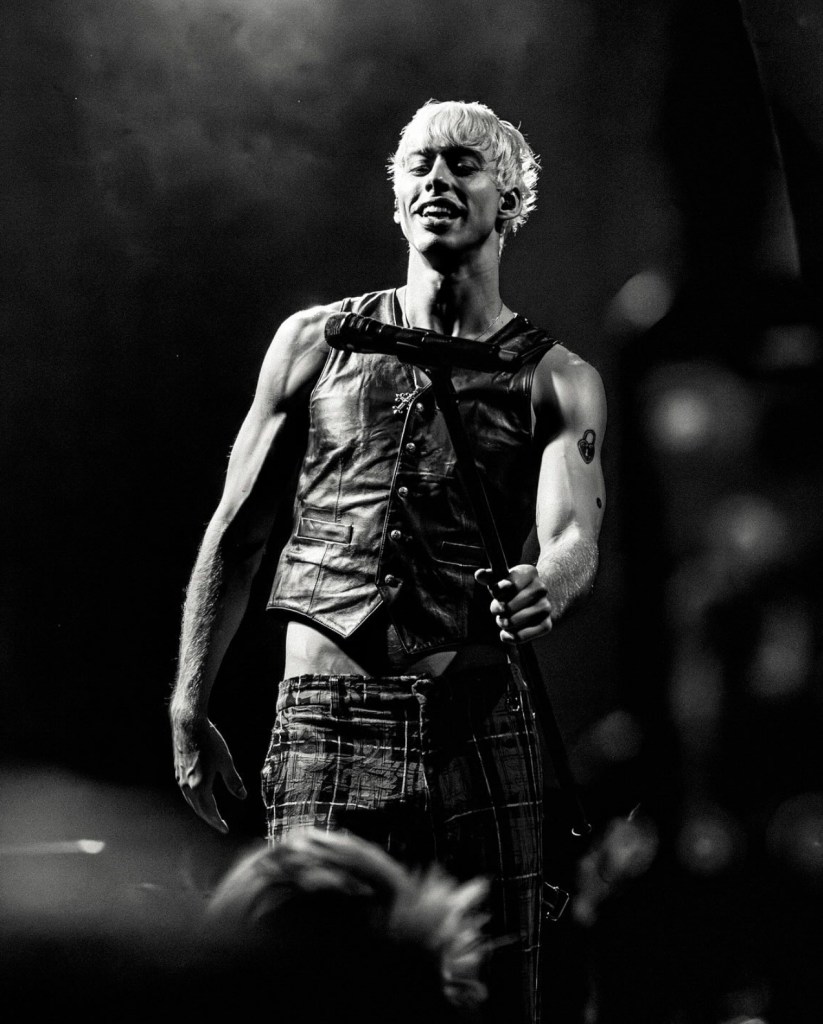

There’s a particular kind of electricity that surfaces when an artist is caught between who they were and who they’re becoming. Speaking from a quiet corner of his apartment, fresh off a sold-out run across two continents, Haiden Henderson embodies that tension with startling clarity; he still says things like “pinch me,” still laughs as though none of it feels entirely real.

At just twenty-three, Haiden has carved out a space in alt-pop that feels both deeply modern and entirely his own: a blend of guitar-driven confessionals, melodramatic romance, and the darkly playful aesthetic that he and his fans accidentally built together. He grew up a self-described “invisible kid,” spent years studying aerospace engineering, nearly took an internship at SpaceX, and only picked up a guitar because the world shut down. He has recently expanded his EP Tension with two new songs: “Chemicals” and “Parasite”, a duet with MICO.

Haiden went into the tour knowing the numbers; he knew it had sold well, but he didn’t know what that would actually look like. Until he stood on stage for the first time as a headliner, he had never played his own shows. Each night widened the world a little more.

He tells me, “I felt increasingly less and less alone in the world as the tour went on. Like, wow, these are my people.”

He remembers looking out each night and seeing groups of “pop girlies that dress more emo than they are,” and instantly recognising himself in them. “That’s so me,” he laughs. It was like discovering a room full of people who already understood the punchlines before he told them, who arrived with in-jokes born in Discord servers and late-night online chaos.

The gifts they brought him were so specific and niche that he finally accepted just how deeply connected his world and theirs had become. “I couldn’t believe how chronically online me and my fans are,” he says, shaking his head. “It was pretty crazy.”

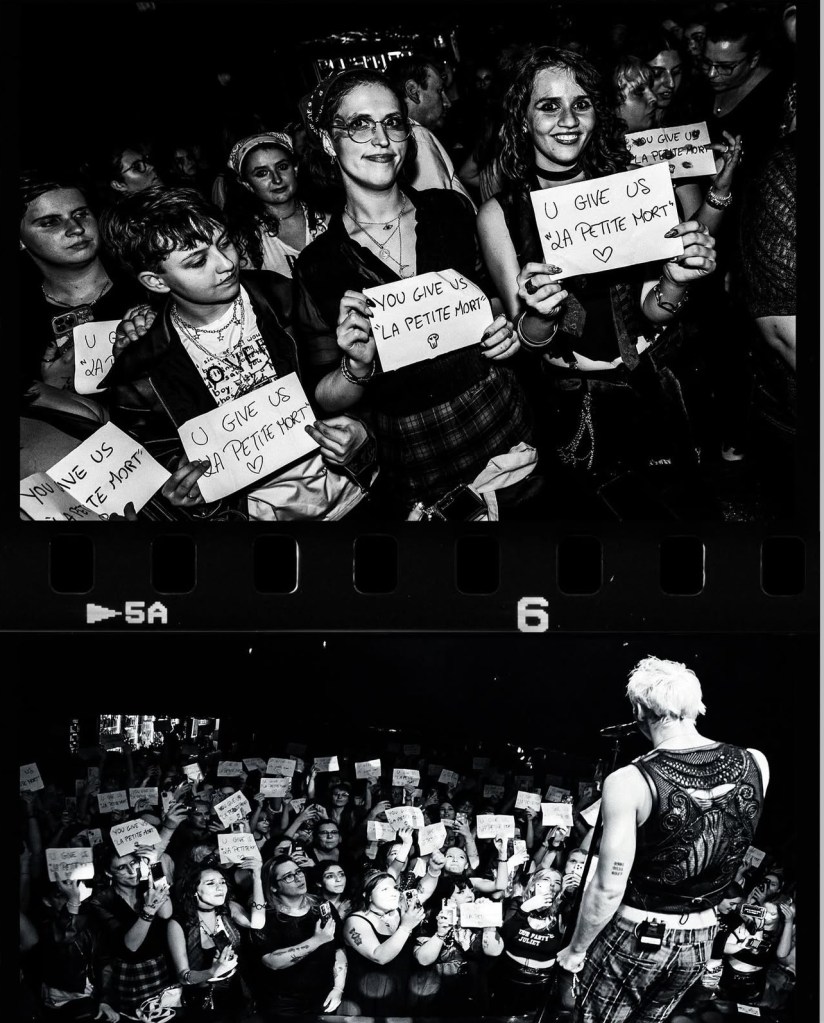

And then there were the signs.

At first, they were playful; maybe a little bold, maybe a little thirsty. But the moment he reacted — visibly, dramatically, hilariously — they became something else entirely. “They did it just to mess with me,” he says. “So that I would have to read the most outrageous and inappropriate things on stage.” The more flustered he became, the more his fans leaned into it, until the signs crossed into territory where they almost needed to be censored online.

“They kind of bully me on stage,” he says, meaning it in the gentlest sense; mutual teasing, affection disguised as mischief, the kind of fandom shaped by not taking yourself too seriously.

“I’m not really on a pedestal,” he says. “Each show feels like a stand-up set almost.” It was the unpredictability he loved, the sense that every night was a little different because the crowd would co-author it with him.

And beneath the jokes and the noise, there were quieter moments too—tiny flashes that made him feel, as he says, “a lot less weird, a lot less alone.” The Discord humour, the semi-ironic vampire obsession, all the small things that travelled with him from screen to stage became points of connection.

“I felt increasingly less and less alone in the world as the tour went on,” he says. “Like, wow, these are my people.”

But touring also forced him to revisit places that held emotional residue from earlier in the year, places tied to the relationship that inspired much of his project, Tension. Performing songs born from heartbreak in the same cities he’d visited during the relationship felt surreal, even cruel. He describes the experience as “the most sinister, evil, ironic version of déjà vu.”

He talks about going to those same countries months later and feeling like a completely different person walking through a version of his old life. “By the end of the tour,” he says, “I felt like I had gone back to war with my emotions.”

And yet, night after night, hearing people sing his words back at him became its own strange medicine. What he thought was too personal turned out to be universal. The more specific he was, the more people clung to it.

He admits he’s always approached songwriting that way — not chasing universality, but chasing the truth of a single moment. “Anything where I’m like, ‘I don’t know if I should say that,’ I try to say it even more,” he says. He writes for the reaction on one person’s face, even when that person is himself.

He doesn’t write often. He writes in waves, only when he’s really feeling something, and even then, the process is nonlinear. “I have to be really compelled to write to write a song,” he tells me. “I can’t just do it out of nowhere.” Most of the time, he’s collecting fragments; tiny beginnings that he tucks away until they ask for more.

“Often, I will write little sections of songs and record them on my phone and put them away for a bit. Then, when I’m feeling a really visceral emotion, something happens in my life, I will go through the folder of sonic ideas that I have and listen to them. Any one of them that jumps out at me as I’m feeling something, I’ll pick and pour my emotions into that idea.”

That’s how Tension was built. He didn’t sit down to write a cohesive project; he stitched together a moment that blew his life open with all the little ideas he’d collected beforehand. “I had a lot of little ideas here and there,” he says, “and then this thing happened in my life that blew everything up, and I picked all these little ideas out, rewrote all of them, kind of puked my story onto them. What came out of that was the whole Tension EP.”

Since coming home from tour, he’s been circling back toward that place where songwriting lives. He says he’s been warming himself up” to write again, journaling a lot, giving himself space to sit with whatever’s underneath. “I journal a lot in general,” he explains. “I go to therapy; that’s a good place to uncover emotions. And just talking to friends, I find out a lot about myself.”

But writing, real writing, the kind that asks for something from him, still feels intimidating. “I have to wait to write songs now until I’m really compelled to,” he says. “I’m a little bit afraid to write, if I’m being honest at the moment.” He also admits that he’s looking forward to overcoming that fear.

That fear, he realises, has been driving him longer than he admits. “I think I’m very motivated by anxiety and fear,” he jokes. “Which is probably a bad thing, but I’ll figure it out later in therapy.” He says this lightly, but it frames something larger — how fear has shaped not just his writing, but the entire path that brought him here.

Before music, he was studying aerospace engineering and had nearly secured an internship at SpaceX. When the pandemic shut the world down, he picked up a guitar, almost by accident, and something clicked. “I could have bumped into a chess piece and become a chess player,” he says. “Anything I did at that moment, I would’ve been obsessed with.”

The sound he’s found since then, the gritty, guitar-driven pop with a shadowy edge, wasn’t designed. It was arrived at. “In the failure to become other people,” he says, “I found where I landed.” He tried being his heroes. He tried shiny pop. He tried normal “poppiness.” But what remained was something darker, something more distorted, something written on a guitar because “that’s the language” he speaks.

He mentions, almost offhandedly, “I don’t think there’s a single song in this project that’s in a major key.” It’s not that he is ‘anti-happiness,’ but happiness isn’t measured in 100% joy all the time; even falling in love has its darker layers.

These darker tones arguably align with the “vampire culture” that he and his fans have gravitated toward. The pale skin, late-night energy, references to “red blood,” and slightly feral jokes all reflect his fascination with vampires, which he says started in middle school: “I watched the hell out of any kind of vampire media.”

He’s leaned into it more recently, incorporating it into show themes: “‘Lovesucker’ is vampire attire, ‘Lips’ was rock star attire, and ‘Sweat’… club clothing,” and in subtle song references like Starters. He enjoys the mysterious and slightly dark side of vampires: “My favourite vampire media… keeps it a little bit mysterious, maybe even scary, but as soon as the vampires are no longer mysterious, it sucks.”

His deeper fascination is with danger as an aesthetic. Liminal office spaces. Tightropes across power lines. The aesthetics of drowning. The Tension album artwork, him lying on the edge of a building beside someone, was an image he’d held in his head long before he knew how to shoot it. “Anything dangerous, taking a single frame out of that, it’s always entertaining.”

But despite his love for cinematic images, the connection that matters most to him isn’t visual: it’s his fans. At first, he was terrified of them, not because of who they were but because being seen was unfamiliar. “I was deeply afraid of messing something up,” he says. Years spent trying to blend in made visibility feel unnatural. But the moment he began sharing the parts of himself he once hid — “my weird hobbies,” his mismatched shoes, his offbeat humour; everything changed. The fans mirrored him. They understood him. And he began to understand them.

A girl in Brussels told him she was getting “the invisible treatment” at school. He knew that feeling intimately. It’s why he wore mismatched shoes as a kid; to be seen at all. The fact that fans now talk to him about their own lives created a strange sense of solidarity he never expected. Since his tour has ended, he’s writing again, albeit “slowly.”

“I want the next project I do to be my first album, and that’s a very scary process. But I think I’m ready for the challenge. I want this next project to be the hardest thing I’ve done. I want it to be the biggest challenge I’ve done. I really want this project to be about letting go of control and just allowing words, stories, and things to come out of me…”

He says it’s not just about the words, though. If you take the words away, strip the song from all language, “does it still make you feel something?” He wants to let go of control enough to surprise himself, to let songs exist before he critiques them. He wants to lean into the R&B and hip-hop he grew up on, and is excited to experiment and continue finding his sound.

It’s about the music carrying him, and letting it carry the rest of us, too.

Haiden apologises for his “rambling” interview; his first real social interaction since choosing reclusiveness after the tour. When I ask what’s next, he says lunch comes first, the rest follows. He doesn’t posture, doesn’t pretend to have it all figured out.

And maybe that’s why people show up with signs, jokes, chaos, and confessions: because he’s already given them permission to be a little unhinged, a little emotional, a little too much. He’s learning to live out loud. They’re learning with him.