On transforming hospital wards into stages, building theatre families where care matters as much as talent, and why live storytelling remains our most essential resistance against forgetting how to feel

When I first spoke to Emma, there was a deep wish for me to share this exceptional woman with the world – therefore an interview seemed almost inevitable. Just a few questions, but it wasn’t enough. You see, after being with such a free spirit, caging her within answers, concise and tailored, was unthinkable if not, somehow, cruel.

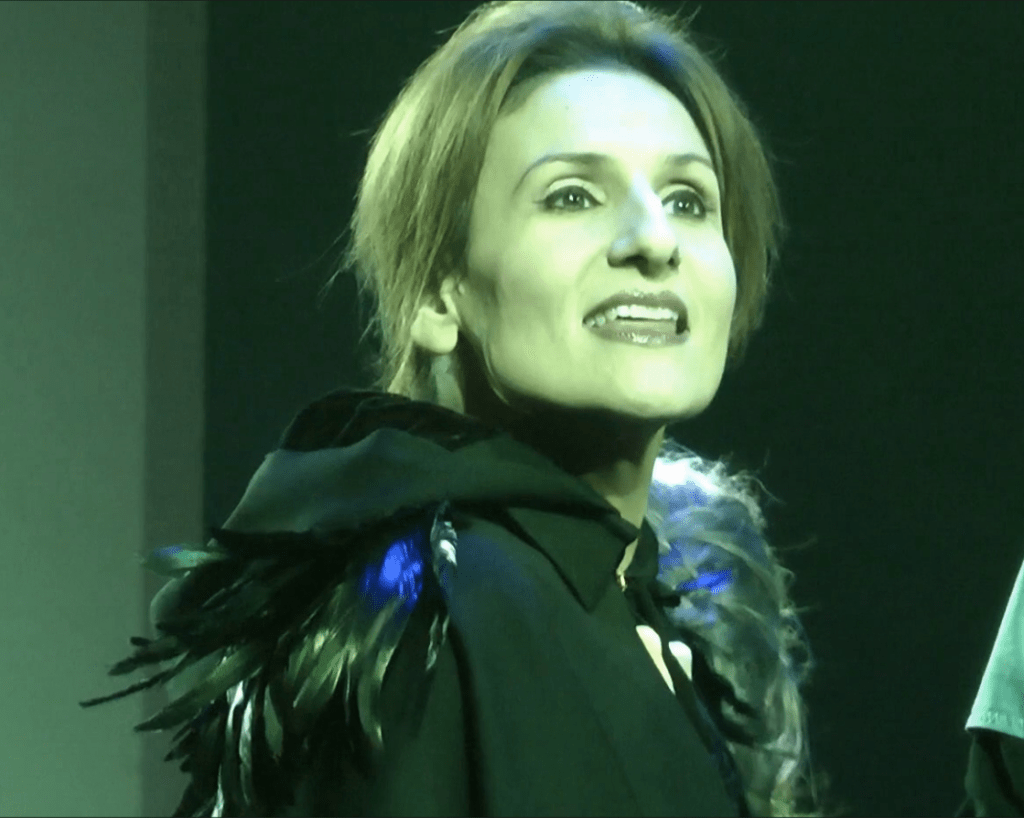

With her company Shadow Road Productions, Emma King-Farlow stages Shakespeare in church crypts and Dickens on cancer wards. She turns colleagues into family, builds rehearsal rooms where disabled artists flourish, and proves that when you design around people’s actual needs, you unlock something extraordinary.

So, the platform is hers, for not even the greatest of writers could ever transmit her thoughts better than this extraordinary artist before me.

‘There was a moment at Charing Cross Hospital that will stay with me forever. We were performing A Christmas Carol on the neurorehabilitation ward, and one of the patients, Peter – a gentleman with dementia – had apparently been in hospital for six months, mostly withdrawn, rarely speaking or joining in with anything. But as soon as the show began, something shifted. He lit up. He started singing along with the carols, commenting on the action with a twinkle in his eye, and just engaging and radiating joy as he did so. A growing number of staff gathered quietly in the corridor just outside to watch him watching us, completely astonished. Afterwards, he posed for photos in one of our top hats – and when we returned the next week to a different ward, they brought him upstairs just so he could see the show again.

Moments like that remind me exactly why we do this work. When someone who’s been silent for months suddenly laughs or sings, it’s not just theatre – it’s healing. I’ve also worked with actors and creatives who’ve said that being involved in a production kept them going during some of the darkest times of their lives. That’s the power of story: it offers a way back to themselves – and being part of a group working hard to create something together can offer you a family.

Sometimes the healing is quiet and personal, and sometimes it’s about bearing witness to shared experiences. In Dreams from the Pit, we worked with and for military veterans. After seeing the show, someone told us they had recognised themselves – and their friends – onstage. They said it had made them realise they needed to get help. That kind of feedback is both humbling and galvanising. We are lucky enough to see at least some of the difference that our work makes in real time.

I’ve always believed that storytelling is a form of resistance and of preservation. Secret Storytellers was born from that belief – that if we don’t preserve and share the stories that matter, the ones that tell hard truths, or offer glimmers of hope, we risk losing not only our history but also our ability to imagine a better future.

We’re living in a time when ‘truth’ feels fragile. As a society, we are overwhelmed by AI-generated images, fake news, algorithmic silencing, and much more. It’s not melodramatic to say that controlling the narrative can mean controlling society, shaping beliefs and behaviour. But theatre – live, human, and vitally rooted in empathy – remains one of the few spaces where truth can still live and breathe in real time, encouraging humanity, community, and hope for better.

There have been dark and dangerous times before – and storytelling has survived them all. Even during the plague years, centuries ago, actors still travelled from village to village, bringing tales that kept communities going, news that kept them connected. Story is the thread that binds us to one another and to our ancestors – our common humanity woven across generations, lessons passed on, hope reborn over and again.

We huddle together in the dark, around a fire, or in a theatre, or at the foot of a hospital bed, and we share stories: to be comforted, to be seen, to find what unites us. In the morning, we rise with new conviction, with new love for and understanding of our fellow humans, and with the dream, however fragile, that the better world we’ve glimpsed in stories could be made real. Stories aren’t escapism from the terrible present. They’re blueprints for a better future – they show us what not to do, what to learn from, what to strive for.

Space changes everything – not just logistically, but emotionally. In a traditional theatre, the audience expects the work to unfold before them; in a hospital or support centre, they’re often not expecting a performance at all. That shift in expectation creates something profoundly intimate, with the smaller space becoming part of the story itself.

When Scrooge is confronted with grief, regret, or redemption, those themes resonate differently in a place where people are literally fighting for their lives, or supporting loved ones who are. There’s a humbling immediacy. More than that, it’s proof of something deeply hopeful: showing that every space, any space, can become a theatre. When a hospital room transforms into a Victorian parlour or the forests of Sherwood, it’s almost like time travel. The IV in their arm, the quiet beeping of a machine, the chair they’re slumped in: all of it becomes part of a moment where simple stories can make the ordinary truly luminous.

The “usual” spaces for theatre were never built for everyone. They were built for those who could afford the ticket, feel comfortable in the audience, physically access the building, or understand the cultural shorthand on display. For me, an “unusual” space is often a more democratic one. A care home lounge, a hospital ward, a garden or library – these are spaces with their own rhythms, their own audiences, and their own kind of power. The act of bringing theatre into those spaces isn’t just logistical; it’s political. It says stories and theatre are for everyone. You belong in this story – and it belongs to you.

When we stage performances in those spaces – when a patient leans forward in their chair or a nurse sings along with a carol – it becomes undeniably clear: these aren’t “unusual” spaces for theatre at all. They’re perfect for it. Because a theatre isn’t really a building, it’s not walls, stages, lights and sound equipment. It’s a group of people gathered together to listen to or watch a story, willing to believe in something together. And that can happen anywhere.

I’m always an artist first, but in healthcare settings the artistry naturally blends with a deep sense of empathy and responsibility. The care is in the details: in adjusting the pitch or pace of a performance when someone looks tired; in making a patient feel seen and included without putting them on the spot; in knowing when a joke will lift the room, or when quietness will resonate more deeply. The care also becomes part of the craft: it’s in the tone of your voice, the structure of your show, the instinctive timing you develop by reading the energy in the room.

I rarely talk about my health issues, but there is no doubt that they have made me fiercely committed to inclusion – not as a token gesture, but as a founding principle. I know how exhausting it can be to navigate systems that weren’t designed with you in mind, to feel that your energy or your health might prevent you from taking part in the things you love. So I’ve tried to build something different: rehearsal rooms that are flexible, production schedules that honour rest and recovery, a company culture where everyone is encouraged to speak up about what they need without shame; where no one has to choose between their wellbeing and their creativity.

I’ve worked with actors who weren’t sure they could still perform because of illness or disability – and then watched them deliver some of the most compelling performances I’ve ever seen. Making theatre accessible doesn’t dilute its power, it deepens it. When you design a rehearsal process around actual needs, rather than an outdated idea of what ‘professionalism’ should look like, you unlock deeper creativity, richer performances, and stronger collaboration. None of this means lowering standards. It means raising the standard of care.

Success is the patient in tears within the first five minutes of A Christmas Carol, overwhelmed not by sadness, but by the emotional release of being drawn into a familiar story full of personal meaning at a dark time when everything else feels unfamiliar. It’s the long line waiting to sign our Visitors’ Book – not just with a ‘Thank you’, but with full paragraphs about what the performance meant to them. It’s a smile from someone who hasn’t smiled in days. It’s the staff asking us to come back, or the nurse telling us that a patient who hasn’t engaged in anything for six months wants to see the show again. These aren’t abstract moments. They’re tangible. Measurable in the emotion – the happiness that lingers after the final bow.

At Shadow Road, the company is never just a group of colleagues – it becomes a family. We prize kindness, flexibility, and mutual respect just as highly as talent. That shapes everything: who we cast, how we rehearse, the tone of the room. It’s never just about who’s best for the role on paper. It’s about how they’ll fit into the rehearsal room, how they’ll lift others up, how they’ll help strengthen the work by making that space feel safe, generous, and uplifting.

We laugh a lot. We check in with each other often. We celebrate together throughout the year, at summer and Christmas parties where everyone brings something to share. The building of a community, a real family, around this small, independent theatre company is a quiet, intentional, and life-affirming thing. Different strengths balance out different weaknesses, and that interdependence makes for better theatre – and better humans.

I endeavour always to create space for individuals to show up as they are, on good days and bad. The end result is a room where those gathered feel they belong, safe enough to take real creative risks, to try things and fail gloriously before landing on something extraordinary. When you feel supported, you can truly shine – and that is reflected in what you can then produce.

If I’m honest, I don’t always make the same allowances for myself as I do for others. I pour a lot into each show – emotionally, mentally, and physically. Last winter, I performed in eight shows over six days whilst extremely unwell. We had no understudy for my role and there simply wasn’t another option – if I’d stepped back, the show wouldn’t have gone on. And when your audience is made up of those facing chemotherapy, living alone in a care home, struggling through a painful recovery, or trying to connect with a loved one they are slowly losing to dementia, you have to show up. There is no other choice – at least not for me.

You show up because you know it matters. You know that the joy and catharsis you’re bringing them might just be the brightest part of their week. Of course, I try to rest where I can. I work with those who look out for me and lift me up when I need it – just as I try to do for them. We debrief after tough performances. We celebrate small wins – and we laugh. There’s such warmth in the work, even when it’s heavy. But what ultimately keeps me going is the knowledge that the light we’re putting out into the world is worth it.

Those moments of recognition usually happen when audiences finally understand the story – the characters and their journey through life, their relationships to each other, the stakes they are playing for – in a way that they haven’t before. Something in this particular telling clicks with them and the language is no longer a barrier, because the emotions become clear enough for the audience to identify and empathise in a way that they perhaps couldn’t before. What once felt distant or intimidating becomes immediate, human and real.

A lot of that comes down to clarity and care in the rehearsal room. It is vital to me to ensure that actors understand exactly what is happening at every moment of the play: what their character is saying, what’s being said to them, what they want, fear, or are trying to protect. We spend real time unpacking the language, the historical context, the psychology – because if an actor doesn’t fully understand something, they can’t possibly communicate it truthfully to an audience.

My work is very character-led. I believe that’s where connection lives. Reviewers and audiences often comment on the emotional authenticity of our productions – particularly in the classics. In Macbeth, for example, I chose to foreground the genuine love between Macbeth and Lady Macbeth, which made their journey far more tragic. As one reviewer wrote, “There is a genuine connection and tenderness… it humanises the couple and makes us actively root for them to succeed.” When audiences see real human beings on stage – not ciphers or academic constructs – the classics stop being something to decode, and start being something everyone can recognise.

For me, accessibility is artistic integrity. Theatre was never meant to be exclusive. Adapting a work so that people can genuinely engage with it isn’t ‘dumbing it down’; it’s honouring what the story is trying to do – and sharing it with as many as possible.

In our Fireside Folktales adaptations, we work with just four actors, which means we have to be imaginative about scale. Instead of spectacle, I focus on intimacy and emotional truth. In A Christmas Carol, we don’t stage the Fezziwig Ball – instead, we explore the preparation for it, and a quiet, revelatory scene between Scrooge and Belle in a side room, during the celebration. The party still exists, just offstage, but the audience gains something deeper: a real insight into who Scrooge was, what he had – and what he lost.

Similarly, in Macbeth, I’ve included new scenes – such as an emotional leave-taking between Macduff and Lady Macduff before his departure – to give real weight to relationships that are often rushed past. When grief comes later, it lands with far greater force. I also like to actively draw the audience into the world of the play. A Herald asking the audience to rise for the King and Queen turns them into the banquet guests. A hand on a shoulder, or shared moment of eye contact, turns an observer into a trusted friend. These choices don’t dilute the work, they clarify it – they invite people in, letting them know that this work is for them, for everyone.

When we performed A Christmas Carol in cancer support centres, hospitals and care homes last winter, we saw tears inspired not only by nostalgia, but by recognition. Scrooge’s journey stops being a tidy moral arc and becomes a reminder that it’s never too late to reconnect, to soften, to hope. In spaces where individuals are confronting loss, fear, or uncertainty, that message lands with enormous force.

In these settings, stripped of theatrical trappings, the classics reveal their rawest truths. They stop being period pieces and become mirrors. For a little while, a hospital room can become Victorian London, ancient Scotland, or anywhere else. That act of shared imagination reminds those watching that their feelings are valid, that others have walked similar paths, and that they are not alone. In moments like that, theatre doesn’t just entertain. It comforts. It connects. And sometimes, quietly, it helps someone to endure.

It can be hard enough to enter traditional theatre institutions when you’re operating from a place of privilege – whether that’s wealth, helpful connections, or simply good health. When you’re not, it can feel almost impossible. That was certainly my experience. So, I stopped waiting for someone else to fire the starting gun on my life and chose to create my own work instead, reclaiming creative agency on my own terms.

That decision led to the founding of Shadow Road. The freedom has been immense: freedom to follow instinct, to respond quickly to real-world needs, and to be values-led without asking permission. I can stage Shakespeare in a church crypt, take Dickens into cancer centres, or fill a centuries-old house with witches and prophecy. I can also choose my collaborators deliberately, including hugely talented artists who’ve taken unconventional paths, who didn’t attend drama school or complete an expensive MA. I care about what a person can do, not which boxes they’ve ticked.

In place of institutional support, I’ve built a community – a theatre family – grounded in shared purpose and mutual care. Everyone contributes according to their strengths. We hold annual gatherings where everyone brings something to contribute, which allow us to reconnect, to welcome new members, to thank our supporters, and to renew the warmth that fuels the work. That sense of collective investment, of connection and family, is priceless.

That phrase – money should not be a barrier – isn’t just a motto. It’s the foundation of how we work. I believe everyone deserves access to stories, to the theatre and all it offers, regardless of whether they can afford it. Practically, that means fundraising relentlessly and creatively: Arts Council grants, local donations, coffee mornings, community events, carol singing – small-scale efforts that also double as outreach and audience-building. We regularly donate tickets to local charities. At the Edinburgh Fringe, we’ve always participated in the Community Tickets scheme. Access has to be intentional – it doesn’t happen by accident.

We also work with extreme care and efficiency. We reuse costumes and props, adapt scripts to suit available resources, and multitask constantly. Limitations don’t dilute the work; they often sharpen it. When every decision has to earn its place, the result is theatre that’s lean, intimate, and purposeful.

Like many artists, everyone in the company has worn other hats. I was a part-time library manager for over a decade, as well as being a published children’s author, and working as an occasional consultant and drama coach. Others have been Fight Directors, archery coaches, teachers, baristas, Netflix subtitlers, and purveyors of beautiful handmade cloaks! That blend of artistry and pragmatism is what has kept each of us afloat.

More recently, I’ve begun building additional income streams that align with the company’s values: monthly Writers’ Retreats, Actors’ Space workshop sessions, and ‘Tea and Talk With…’ events at our small rehearsal space. Individual productions are funded through a patchwork of ticket sales, grants, crowdfunding, donations, and in-kind support. Nothing is wasted. Everything is shared and reused. Sustainability, for us, is about adaptability and trust.

My dream is that one day everyone involved can be paid enough to give up their other jobs and devote themselves fully to the work they were born to do. Theatre should be for everyone – on both sides of the curtain.

I think we’ve all emerged from the pandemic with a more visceral understanding of how much communities need connection, hope, and meaning. For Shadow Road, that didn’t change our direction so much as confirm it. What we were already doing suddenly felt not just relevant, but urgent.

What we do isn’t just theatre; it’s care. Care for old stories that still have vital lessons to teach. Care for those who can’t access traditional theatre spaces. Care for artists navigating illness, disability, burnout, or precarity. And care for society itself, more vital than ever at a time when empathy feels under real threat.

Social media, polarisation, and algorithm-driven outrage have drastically reduced our capacity to understand one another. Theatre does the opposite. Like books, it trains the imagination. It allows us to step into someone else’s life – to feel their grief, their joy, their fear – and to come out changed. That act, in itself, is community care.

Looking ahead, I want to build stronger infrastructure around this work: deeper partnerships with hospitals and hospices, expanding our programmes, developing long-term relationships with community venues. I’m also keen to establish an ongoing touring strand specifically focused on care settings. We’ve proven that we can take our Fireside Folktales productions – shorter, flexible, low-tech shows – out to meet individuals where they are, whether that’s a ward, a waiting room, or a wheelchair in the corner. I’d like us to be able to do that all year round, not just at Christmas.

If care became central to theatre rather than marginal, the entire ecology would shift. We’d start asking different questions: Who is this for? Who isn’t here yet – and why not? Rehearsal processes would become more flexible. There would be greater openness to difference – neurodivergence, disability, chronic illness, mental health – not as problems to manage, but as realities to work with creatively. The industry would need to value work and impact over pedigree, making space for artists who didn’t go to the ‘right’ schools or come up through the ‘right’ buildings.

Care doesn’t mean compromise. It means clarity of purpose. It means theatre that understands why it exists and who it serves.

Opening up theatre to as many as possible looks like walking into a cancer support centre with a handful of props, a few costumes, and four actors and transforming a day for someone who thought happiness was out of reach. A care home resident smiling for the first time in weeks. A child dancing with the Fox or Grasshopper and squealing with glee. A Veteran seeing themselves on stage and deciding to ask for help.

It means not waiting for communities to come to us, but meeting them where they are. Performing in gardens, libraries, churches, town halls, hospital corridors – any space willing to hold a story. It means adapting the scale, not the soul: emotionally rich work that’s logistically light, flexible, and responsive.

It also means practical access – free and low-cost tickets, donating seats to charities, participating in community schemes not as a gesture, but as a core principle. And it means acknowledging that once a show is viable, there is a choice: whether to maximise profit, or to accept a little less in order to reach those who would otherwise remain excluded. In that context, success can be measured not only by the size of the return, but by what becomes possible when we choose to let more people in.

If more decision makers – funders, policymakers, producers – truly understood this, theatre could again become what it was always meant to be: something that belongs to everyone.

At the heart of all this is my deep and growing conviction that theatre matters now more than ever. We are living in a world that feels increasingly fractured – where empathy is eroded by outrage-driven media, algorithmic echo chambers, and the constant pressure to measure worth in money, power, likes, or visibility. Something essential about our shared humanity is being worn away.

Stories are one of the few forces that reliably restore it. Reading does this – but theatre does it even more powerfully. You don’t just imagine another life; you witness it. You see the hurt, the tenderness, the fear, the hope in another human being’s face. You experience it alongside others. And in that shared act of witness – laughing together, crying together, recognising something true – connection is rebuilt.

Theatre also safeguards something else that feels increasingly fragile today: truth. It preserves old stories and makes room for new ones – stories that convey history, morality, resistance, and hope. Throughout history, those in power have tried to erase or rewrite them, because whoever controls the stories shapes those who hear them and thus the society they all live in. In an age where AI can fabricate any image or recording, where voices and labour are increasingly treated as disposable, live theatre offers something inimitable: real human beings, in real space, telling stories to one another. Around a fire. In a church. By a pond. Without mediation. Without filters.

That belief underpins everything I do – from Secret Storytellers to Shadow Road’s work in care settings, and now the Fireside Folktales Fringe: a festival built to safeguard space for storytelling that is intimate, low-tech, human, and accessible. Storytelling that invites individuals in, rather than locking them out. That keeps a light burning, even – especially – when the world feels so dark. I won’t pretend that any of this is easy, but championing this kind of work, and ensuring it continues to be shared with as many as possible, feels less like a choice than a real responsibility, now more than ever.’

There is a kind of courage that doesn’t announce itself, that doesn’t seek recognition but gives endlessly because the act of giving is itself the purpose. Emma’s work reminds us that art doesn’t exist to gratify the artist – it exists to fill what is most starved in those who receive it. To stay loyal to that truth, to persist despite struggle, requires a depth of conviction most of us can barely fathom. Yet maybe that is precisely where the meaning lies: not to fully understand, but to witness, to breathe, and to consider what it means when someone chooses to keep a light burning – not for themselves, but for all of us stumbling through the dark in search of what we are, ultimately, in essence.