The award-winning Italian filmmaker has worked on films with Christopher Nolan and Peter Greenaway and directed music videos for Moby. When lockdown hit, he created ‘Illustrated Cinema’, a handmade technique that captures the sweet and the macabre: childhood aesthetics transformed into darkly subversive, profoundly unsettling art.

There’s something you need to know about Matteo Bernardini before we begin. When I spoke to him, I thought I had met Peter Pan.

Not the idealised Disney version. The real one. Wide-eyed and gleeful, with a laugh so contagious it feels like flight. A man for whom life continues to amaze, to delight, to astonish, as if he’s discovering everything for the first time, perpetually.

Yet, here’s what makes Matteo extraordinary: unlike Pan, who refuses to grow up, who turns cruel when faced with Wendy’s transformation into adulthood, Matteo has done something Pan never could. He’s carried childhood through. Not as nostalgia. Not as retreat. As a living creative force that reveals the darkest truths about what we become when we think we’ve left it behind.

His ‘Illustrated Cinema’, paper theatres, watercolours, fairy-tales, gingerbread-men, made me writhe uncomfortably in my seat. It made my childhood erupt before my eyes in the midst of pure grief and personal vulnerability. It confounded me. Matteo has harnessed the very essence of why we are as we are. Our childhood. And he’s using it to show us who we’ve become.

It started, as so many revelations do, from survival.

Northern Italy, 2020. The first COVID lockdown hit harder there than almost anywhere else in Europe. Matteo Bernardini, filmmaker and illustrator, a man who’d spent his career making live-action films, found himself locked inside his house for months.

“I had to literally throw several projects out the window,” he tells me, and I can hear both desperation and liberation in his voice. The live-action films, the crews, the productions; all of it abandoned. Impossible to continue.

For years, he’d been asking himself a question: Is it possible to make something cinematic entirely on your own? Cinema is collective by nature. He loved that. Still does. Anyone who’s pursued this path knows the waiting, the depending on others, the projects that fade into oblivion before they ever see light.

And then the pandemic forced the answer.

Shut indoors with nothing but his desk, he started playing. “Since I’m not an animator, I didn’t know the techniques themselves,” he explains, “so I came up without really having any sort of pioneering intent, but I literally started just playing around and experimenting.”

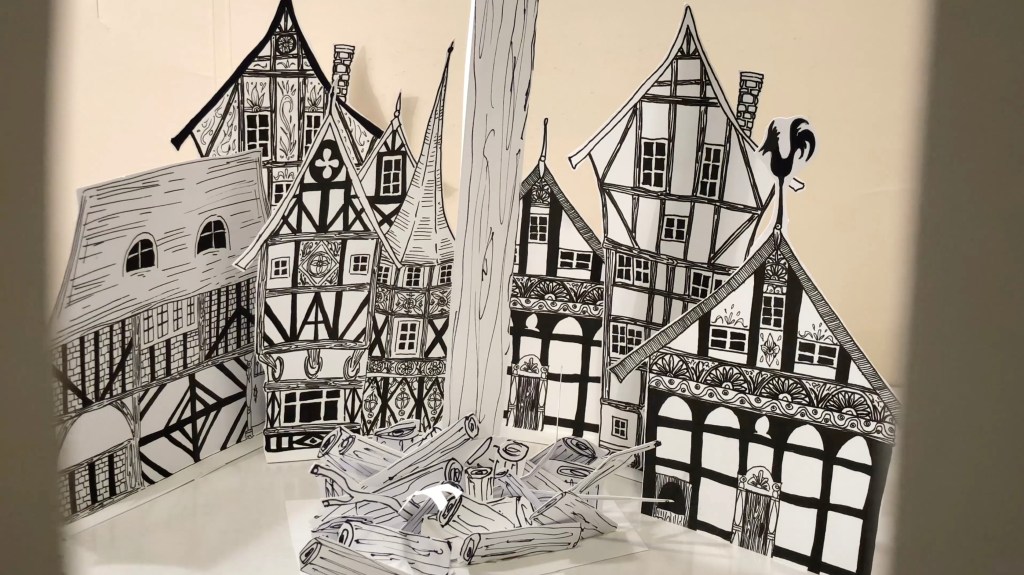

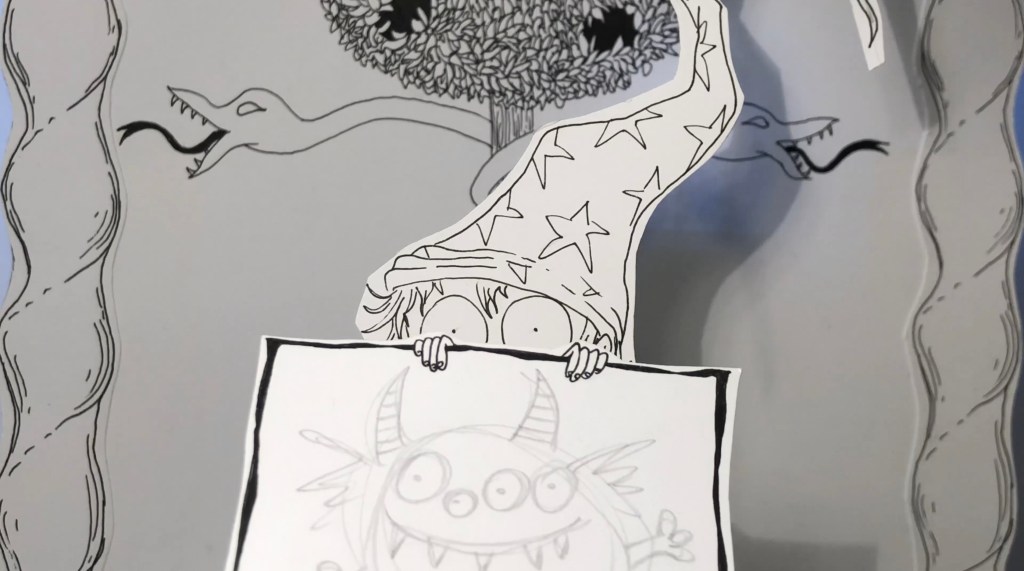

What emerged was something he would eventually call ‘Illustrated Cinema’, a technique closer to drawings coming to life than to classical animation. Paper, scissors, glue, watercolours. Handmade. Rough textures. Visible brushstrokes. Everything the modern viewer’s eye has been trained not to expect in an era of digital polish.

He created The Little Broomstick Rider, a short series about a nine-year-old boy happily admitting to witchcraft, standing trial; persecution wrapped in the childlike aesthetic of paper theatres. He sent it to Slamdance Film Festival. It won the Audience Award.

“It felt like a rebirth, really,” he says, and I understand completely what he means. Not a return to something lost, but a discovery of something that had been waiting all along. “I don’t want to sound too philosophical or metaphysical, but really it was a very refreshing new starting point.”

The lockdown gave him something unexpected: complete creative isolation, yes, but also boundless creative freedom. No one to wait for. No approvals needed. No compromises required. Just paper and scissors and glue and the stories he wanted to tell.

It’s political, this choice. More political than it might seem at first. As Matteo puts it: “The ‘Illustrated Cinema’ technique itself can be seen as a political gesture.” Making cinema entirely, or almost entirely, on one’s own. Creating autonomy within an industry built on interdependence.

I’m getting ahead of myself, though. Understanding HOW he works doesn’t yet explain WHY his work makes you feel the way it does. Why paper and watercolours create genuine horror. Why I sat watching his films feeling mentally and emotionally disjointed, hovering, as I told him, “in what I can only describe as a fantastical dimension between the insane and the uncannily true.”

He smiled when I said that. That Pan-like mischief in his eyes. “That’s exactly part of what I wanted to achieve,” he said.

Santa’s Helpers’ Troubled XMas, an animated series, began, improbably, as an advent calendar. Thirteen years ago, on the evening of December 1st, Matteo had a sudden idea. He spent the rest of the month painting watercolours. One each day. Twenty-four illustrations, each depicting one of Santa’s little helpers being gruesomely killed by an inanimate, Christmas-themed object. As December 24th approached, the splatter level increased.

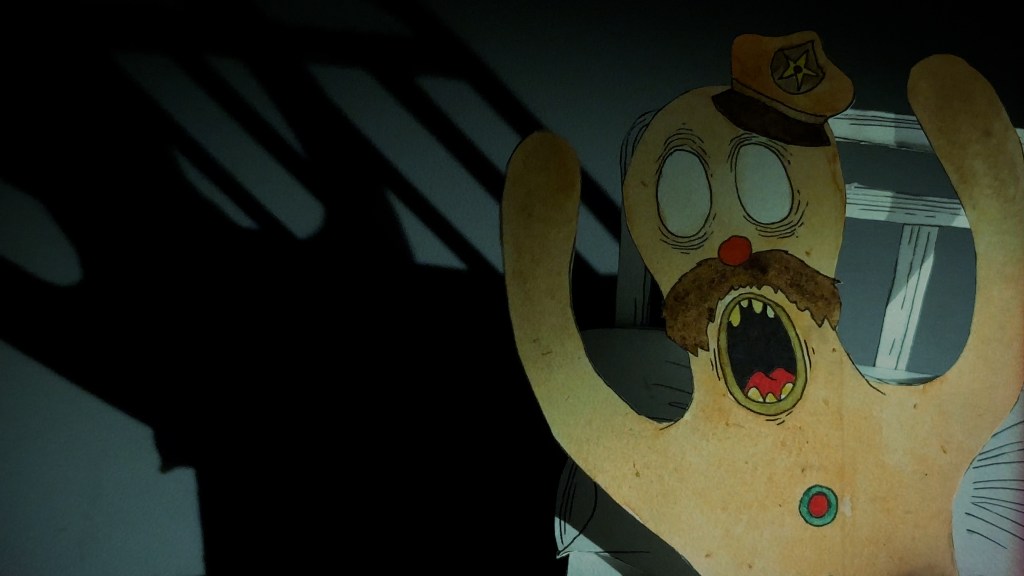

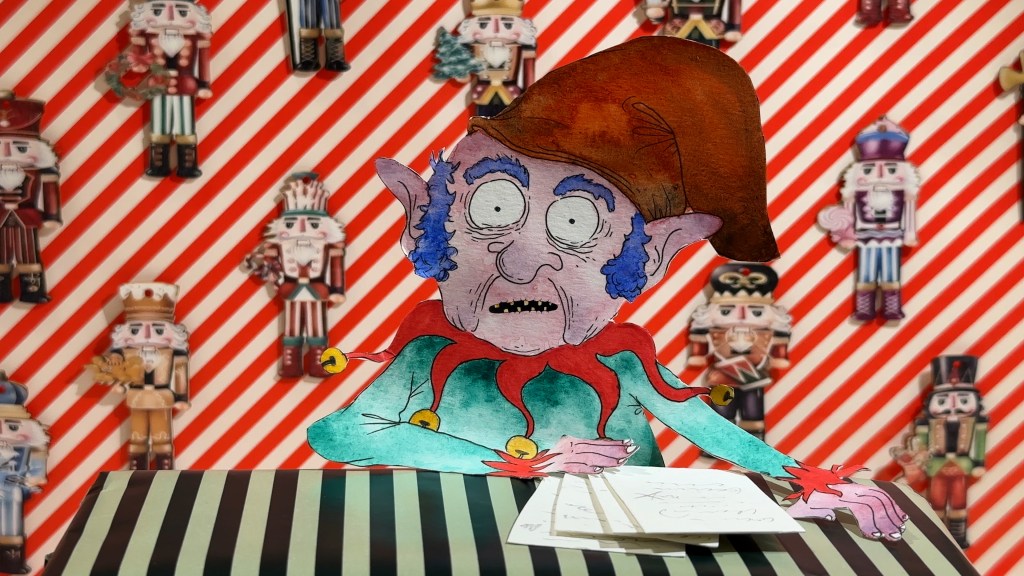

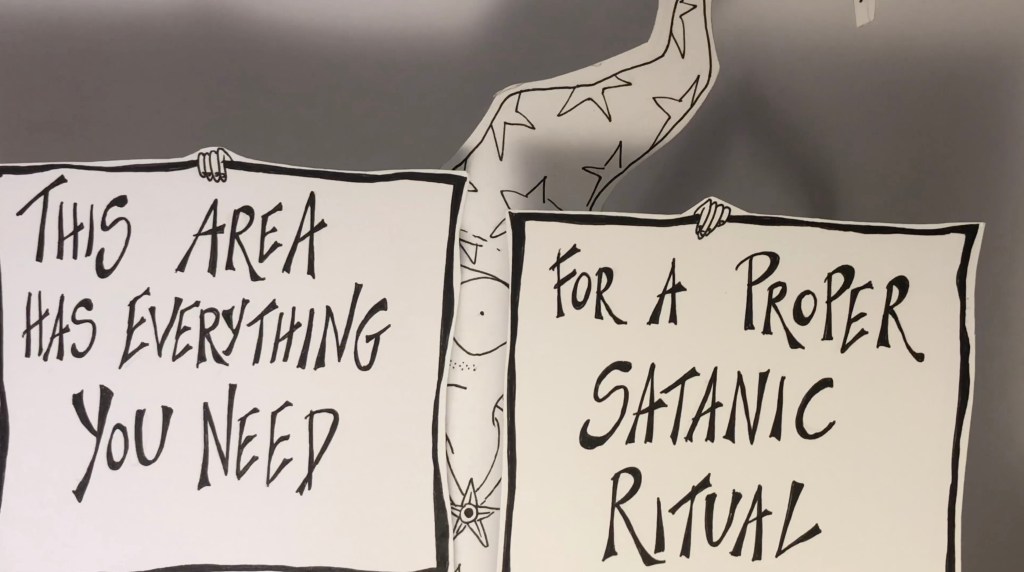

It was successful. Astonishingly so. “Both among people who loved Christmas but had a good sense of humour, as well as people who detested Christmas for all the obvious reasons,” he tells me. When he finally turned it into his animated series, he had a narrative framework to build: a gingerbread-policeman investigating murders, workplace deaths of poor labourers, turbo-capitalist greed, the City of Christmas in the hands of billionaire industrial tycoons.

Why gingerbread-men screaming shouldn’t be so visually disturbing, but are, and why paper and watercolours manage to create genuine horror.

The gingerbread-man is screaming. His paper body is mangled, painted blood seeping across the frame while ‘Hark the Herald Angels Sing’ plays somewhere in the distance. I should laugh. It’s absurd, childish even. I don’t. I can’t.

Something crawls beneath my skin and stays there.

When I tell Matteo about this sensation, about the profound discomfort his work creates, he nods, recognising exactly what I mean, and I realise I’m watching someone who has discovered how to make tenderness more powerful just by destroying it.

Film noir meets paper theatres. The hardboiled detective aesthetic of Raymond Chandler refracted through E.T.A. Hoffmann’s uncanny Gothic tales and H.P. Lovecraft’s cosmic dread. All rendered in watercolours and cut paper.

“I believe it stems from the juxtaposition of absolute tenderness with extreme, graphic violence,” he explains. “I have found that when these two elements are combined, they create an explosive mix, especially, and perhaps above all, on a humorous level. One could say they are ‘the perfect recipe for comedy:’ a decidedly black form of comedy indeed.”

Black comedy. Yes. Yet there’s more happening here than just humour. The handmade quality matters. At a time when the viewer’s eye has grown accustomed to digital expertise, Matteo’s camera captures textures that are markedly rougher and rawer. The surface of the paper is perceptible. Brushstrokes are visible. Gradients and runs of colour bleed into each other. “I assume all of this helps to suggest a semblance of realism within a context that is, in fact, entirely unreal,” he tells me.

I think of the elf wrapping empty boxes for the perfect Christmas, creating backdrops with no depth, teaching us how to decorate while being murdered. The snowman and nutcracker watching, powerless. Baby Jesus giving interviews with barnyard bodyguards while ‘Hark the Herald’ plays and violence unfolds nearby.

Beautiful surfaces hiding systemic horror. Diplomacy masking inefficiency. Festivities as facade.

“This series can very much be read as a metaphor for our times,” Matteo tells me. “Turbo-capitalist greed, workplace deaths of poor labourers, initially dismissed as accidents but soon revealed to be something else entirely. All of this is meant to carry a distinctly political charge.”

He’s careful, though. The risk of overtly political works are becoming “rather sterile pamphlets.” So he builds a dense plot and strong atmosphere first. Entertainment and emotional engagement on the surface. Symbols and underlying meanings beneath, not always immediately apparent.

His short film, The Little Broomstick Rider works the same way. A nine-year-old cheerfully admitting to witchcraft. A child’s trial. Childlike form carrying the heavy weight of historical witch hunts, of real violence against real people.

Why does simplicity amplify horror rather than diminishing it? Childhood materials depicting adult violence creates a double transgression. We’re programmed to protect the innocent aesthetics of our youth. Seeing them violated feels like watching our own innocence being murdered.

Which, of course, is exactly what growing-up is. And Matteo understands this. He’s always known this.He grew up with the artists who understood it too.

Edward Gorey. Age eleven. A friend’s house. Matteo accidentally found a book, instantly fell in love, and begged his parents to buy it for him. Too young, perhaps, for Gorey’s macabre gothic world, but that didn’t matter. He’d found a visual language he already understood: the juxtaposition of the innocent and the terrible, rendered in pen and ink.

Before Gorey, there was Roald Dahl and Quentin Blake. The Witches. The Twits. George’s Marvellous Medicine. Narratives that made him laugh while quietly disturbing him, black humour that felt like permission to see the world’s contradictions without flinching.

And there was his aunt, no longer alive, but fundamental to his upbringing. She gave him wonderfully rendered books, beautiful editions with masterful artists. Not just stories but visual feasts. She showed him early that pictures and words together create a power neither can achieve alone.

These weren’t accidents. These were formative encounters with artists who understood what Matteo would spend his life exploring: childhood forms can carry the heaviest truths.

We’re sitting in that space between our virtual conversation and his films, talking about why fairy-tales matter. Why they work. Why stripping them of their disturbing elements fundamentally misunderstands what they are.

“Fairy-tales at the beginning, yes, were meant for a younger audience, but this pretence of having to refer the fairy-tale exclusively to a younger audience is rather new in history,” Matteo explains. “At the very beginning, fairy-tales were made for a collective group gathering around a fire, possibly at night, entertaining one another with these kinds of stories.”

I think of this image: firelight, faces young and old, a story unfolding. Adventure and fantasy, but also horror, thriller, even eroticism. Everything human experience contains, distilled into narrative.

The modern tendency to “cocoon fairy-tales around children,” as Matteo puts it, deprives them of their most disturbing aspects. Those aspects were necessary, though: the advancement of a character through life, wonderful things and atrocities, obstacles to overcome.

Not all original versions of fairy-tales end well. Hans Christian Andersen knew this. The Little Mermaid doesn’t get her prince. She becomes foam. Dissolves into sea spray and light. I mention this to Matteo, how the romanticised version had always felt like a betrayal, and his face frowns in thoughtful recognition.

“Tragedy doesn’t make them bad,” he says, “that just makes them very, very interesting. And real.”

This is what I’m beginning to understand about Matteo’s work. He’s not using fairy-tales despite their darkness. He’s using them because of it. They were whole before we began cutting them down to fit our anxieties about childhood innocence. And Matteo is making them complete again.

There’s another dimension manifesting in Matteo’s work beyond the reclamation of fairy-tales: the way he refuses to give you easy answers. The way his films leave space for interpretation, for multiple readings, for questions that linger long after the screen goes dark.

“It’s very important that the audience makes up their own minds,” he says immediately, as if this has always been central to his practice. “Most masterpieces share one characteristic, which is, of course, that of ambiguity. A work of art that never stops questioning you.”

I think of the gingerbread-man screaming, the elf wrapping empty boxes, the gingerbread-policeman entering the killer’s mind with no resolution. Each image opens enough to contain multiple truths. Political satire, yes, but also personal grief. Childhood terror and adult recognition. The sacred and the profane existing in the same frame.

This capacity for multiple readings didn’t arrive by accident. Matteo’s background is the written word, not film. His education was steeped in Greek, Latin, and comparative literature; training in how the same story transforms across cultures and time.

What fascinates me is how this shaped his visual work. He absorbed different narrative traditions through reading, let them settle into his creative consciousness, and then brought them forth through images rather than words.

“I would say that I was raised inadvertently in a British way through reading,” he says, despite his parents not speaking English but French. “My main creative sources have always been, yes, books, but also visual arts: paintings, illustrations, photography.” Then, almost as if in contemplation he adds “Rather than films, I would say.”

He’s been rediscovering nineteenth-century German writers. E.T.A. Hoffmann, Ludwig Bechstein. Those who understood fairy tales could be vehicles for the uncanny, the psychological, the deeply strange.

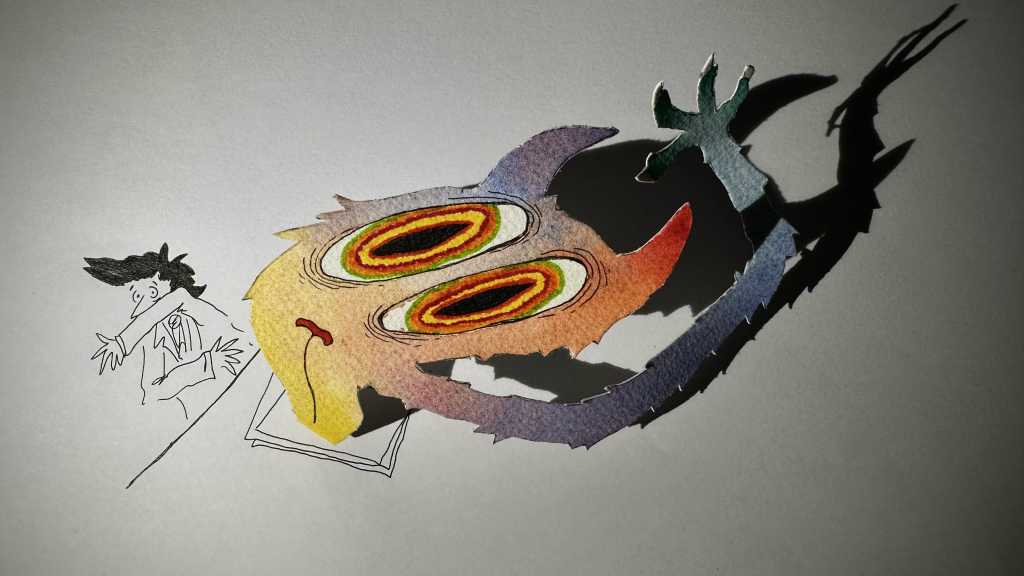

Kreismurriana is his homage to Hoffmann, created for the 250th anniversary of his birth. An animated phantasmagoria inspired by The Life and Opinions of the Tomcat Murr and Kreisleriana. Hoffmann’s own sketches from Bamberg and Berlin archives brought to life through Matteo’s ‘Illustrated Cinema’ technique.

I watched it disoriented, exhilarated. The pace is ferocious, matching Schumann’s compositions inspired by Hoffmann’s works. The erratic composer morphs into a macabre, giant cat, inseparable. Fast, furious, deliberately overwhelming.

This is what happens when the written word meets visual art meets music. Work that operates on multiple levels simultaneously. Political and personal. Comic and tragic. Clear and ambiguous.

Matteo Bernardini has found a way to make us question images the way great literature does. Work that refuses simple interpretation. Work that transcends.

But there’s something else. Something I haven’t told you yet. Something that goes deeper than the political critique, darker than the fairy-tales, more personal than anything I’ve described so far.

There’s one short film I’ve been circling around, one work I’ve held back because of what it did to me. What it revealed.

It has nothing to do with paper or watercolours. It has everything to do with childhood, with loss, with the thing we all carry but refuse to name.

That story requires its own space. Its own grief. Its own telling.

And it’s waiting.

ABOUT MATTEO BERNARDINI

The Little Broomstick Rider won the Audience Award at the 2021 Slamdance Film Festival and received its UK Premiere at London FrightFest, where the international press defined it as “one-of-a-kind,” “a must-see,” and “witty, surprising, and politically pointed.” His work has screened at festivals worldwide, and the Cinergia Forum of European Cinema in Lodz, Poland, organised a retrospective of his narrative works.

Since 2016, Matteo has taught Film Directing and Production at Scuola Holden (the creative writing school founded by novelist Alessandro Baricco) in Turin, Italy, and has lectured on Filmmaking and Opera History at the University of Hamburg.