His short film is the only faithful screen adaptation of J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan true ending . A meditation on childhood, bereavement, and growing-up: how the filmmaker carried The Fairy-Tale through without remaining heartless.

In my previous conversation with filmmaker Matteo Bernardini, I traced the origins of his ‘Illustrated Cinema’, the handmade technique of paper, watercolours, and fairy-tale forms through which he creates work that is politically charged, darkly comic, and profoundly unsettling. His work embodies childhood aesthetics harnessed with adult understanding.

But there is one work I haven’t told you about yet. The one I carry very close to my heart. The one that has nothing to do with paper or watercolours at all.

An Afterthought.

The story of Peter Pan has always been a relentless voyage into my childhood subconsciousness. Watching Matteo’s rendition made it all resurface unceasingly. The weight of it, the emotional force, rendered me vulnerable in ways I had forgotten.

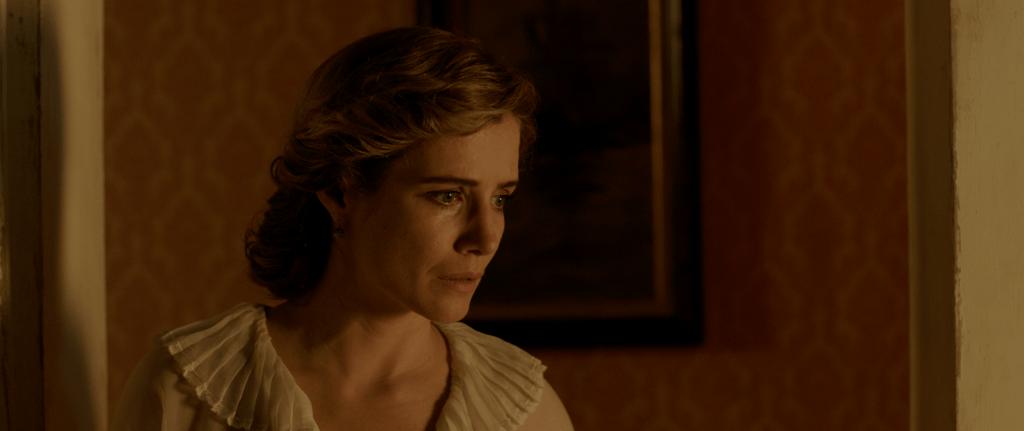

Wendy is a woman now. A mother. The window to Neverland still open in her old nursery, where her daughter Jane sleeps. And then Peter returns.

He hasn’t aged. He never will. Wide-eyed, eternal, untouched by time. Wendy has, though. She’s a mother now, a wife, an Edwardian angel of the household. She’s built a life, a role, a credible existence. And in the instant Peter flies back through that window, it all disintegrates.

She hears Jane laughing, dancing in the air as she flies with fairy-dust. Peter turns to Wendy with the cruelty only eternal children possess. “She is now my mother,” he says.

Bewilderment. Deep heartbreak. The girl who once flew with him, replaced. Discarded. Forgotten.

I watch as Jane rises, takes Peter’s hand, flies toward the window. And Wendy becomes like a light. Further and further away into nothing. Fading. Dissolving. While her daughter disappears into the night sky.

Mahler’s Fourth Symphony plays. It rips you to shreds.

This is a double grief, I realise. Wendy isn’t just losing her daughter to Neverland. She’s losing her own childhood all over again. The girl she was, the adventures she had, the magical boy who loved her before time meant anything. Does childhood really turn into nothing? Does it stop existing?

Matteo Bernardini’s short film An Afterthought is the only faithful screen adaptation of this ending. “The main themes, and the main atmospheres, and the main emotions that transpire from the pages of Peter and Wendy by J.M. Barrie, have never been told on the screen,” he tells me with absolute conviction. “Never. Ever.”

When I tell Matteo about the loss I felt watching, he understands immediately. “The double layering was entirely intentional,” he says.

Of course it was.

“I have always regarded Barrie’s masterpiece as ‘an essay on ambiguities,’” he explains. “I consider it one of the great literary works of the twentieth century, and I wanted to pay it proper tribute through my adaptation.”

Peter Pan has never been what we think it is. Not the Disney boy who won’t grow up. Not an adventure story for children. It’s about something much darker, much more complex.

“The cyclical element is deeply inscribed in the novel’s DNA,” Matteo tells me. “Wendy follows Peter to Neverland, her daughter will do the same, and after her, her daughter’s daughter.” Mothers letting go, again and again, every generation. The loss repeating like a wound that never heals.

But here’s what destroys me: Barrie’s novel ends on a single word. “Heartless.”

To take flight, you must be “gay, innocent, and heartless.” All three simultaneously. That’s what children are. That’s what Peter remains. And that’s what Wendy can no longer be.

Peter’s tragedy is eternal solitude. His decision to remain a child means he renounces life and its cycle. He’s doomed to lose everyone he loves, first through their passage into adulthood, then through death. Worse still, he has no sense of time, no memory. He lives in eternal present. He will never learn. He will never benefit from his own experiences.

“Unlike those protagonists so dear to the hero’s journey and to classical narrative arcs, Peter Pan never evolves,” Matteo says. “He remains forever identical to himself. This is his most defining trait, and also his condemnation.”

An Afterthought is only the epilogue, a short film that can stand alone. Matteo has the entire film in his head. The script is ready. He’s been dreaming of making this film since he was a child who wanted to become a director. It will take time, resources, and the right collaborators. He will make it, though.

On the occasion of the short film’s international premiere at the Giffoni Film Festival, he showed An Afterthought to an audience of children aged nine to twelve. They loved it. They weren’t traumatised. They understood it in the way children understand things, on multiple levels at once.

Children know. They know childhood doesn’t last. They know loss is coming. They know growing-up means leaving something precious behind.

Adults are the ones who pretend otherwise.

Matteo isn’t pretending. He’s made a film about what actually happens when childhood ends. Not a gentle transition. Not a happy evolution. A severance. A girl who flew once, grounded forever, watching her daughter disappear.

And somehow, Matteo has made visible what we all carry invisibly. A short film. A woman fading into shadows, music that engulfs you, a window left perpetually ajar.

Because childhood doesn’t end. It transforms into absence. Into the ache of watching someone else fly toward the window you once climbed through. Not a memory we can revisit, but a light we watch disappear. The wound we inherit simply by growing-up. The loss that makes us who we become, regardless of where our destinies lead.

What Matteo has done becomes clearer now.

Peter Pan chose eternal childhood and paid with eternal solitude, doomed to lose everyone he loves without memory or growth. Wendy chose adulthood and lost the girl who flew, watching her daughter vanish.

These aren’t just fictional losses. They’re the two paths we’re taught to believe are our only options: refuse to grow up and remain heartless, or grow up and lose everything magical about who we were.

Matteo has found a third way.

He’s carried childhood through. Not by refusing to grow, like Peter. Not by surrendering it completely, like Wendy. He’s integrated it. Transformed it into a living creative force that doesn’t just remember innocence but uses it to reveal uncomfortable truths about what we become.

This is what his work shows. His work embodies childhood aesthetics harnessed with adult understanding. Santa’s Helpers’ isn’t nostalgia; it’s fairy-tale forms carrying political critique. An Afterthought isn’t Peter Pan retold; it’s the grief of growing-up made visible so we might finally understand what we’re mourning.

What if fearing the loss of innocence is just a stepping stone? What if it’s meant to lead us toward something else entirely: the true, bare understanding of the human state of being?

His work embodies this. He hasn’t abandoned the wonder, the delight, the astonishment. He’s just added layers. Depth. The capacity to see beauty and horror simultaneously. To hold tenderness and violence in the same frame. To refuse easy answers while creating work that questions us endlessly.

Matteo himself understands this paradox. As he puts it, preserving the childlike quality — not childish, but childlike — comes with time and experience.

He pauses, then adds with a smile: “And here Time returns, as a theme. Ironic, considering that we are once again talking about Neverland and Peter Pan-related themes, isn’t it?”

Time. The one thing needed to learn how childhood survives.

Children understand his films because they already know the darkness exists. Adults struggle because we’ve convinced ourselves we had to leave something behind to become who we are.

We didn’t, though.

Matteo is living proof. His ‘Illustrated Cinema’, his An Afterthought, his entire creative practice demonstrates that childhood doesn’t vanish when we grow up. It transforms. It becomes the lens through which we see clearly, the force that drives us to make visible what others refuse to acknowledge, the bridge between innocence and experience that lets us hold both without destroying either.

He is Pan who grew-up without becoming Wendy. The boy who never forgot without being the boy who never grew.

And in showing us this, in making us feel the discomfort and the grief and the wonder all at once, he’s revealed something essential: growing-up doesn’t mean losing childhood. It means learning how to wield it.