From her grandfather’s garden to the illustrated pages in her children’s hands – every seed tells a story of return.

Jenan Matari is an award-winning Palestinian storyteller, author, and producer, amplifying Indigenous Palestinian voices and weaving narratives of existence and survival into advocacy. She spoke with neun Magazine about the importance of acknowledging Indigeneity, lenses of colonisation, and the power of farming and oral storytelling. Through her words, resistance blooms softly: in language, in legacy, and in love.

Your Instagram proudly shares that you are an award-winning Palestinian ‘hakawati.’ Can you tell us more about what it means to be a hakawati, both literally and symbolically?

Hakawati is the Arabic word for storyteller. Storytelling has always been a cornerstone of Arab and Indigenous culture. As Palestinians, we are part of the Arab world, but we are also an Indigenous people native to historic Palestine.

The reason our Indigenous traditions and histories have been preserved for thousands of years is because of storytelling. We are oral storytellers; we keep history alive by passing it down through generations, whether through art, dance, or song.

It’s not just a symbolic or ‘whimsical’ tradition where we’re sharing beautiful stories or ensuring that parts of our tragic history are not forgotten; it’s a form of survival for Indigenous people.

Today, when Palestinian stories are finally reaching a global audience, we’re witnessing how this tradition shapes awareness of what it means to be Palestinian and what has been happening in our homeland for the last century.

Our stories are our survival. Many of the most prominent Palestinian voices today are journalists and storytellers. It’s powerful to see this tradition finally being recognised, not because we needed Western or mainstream validation, but because it’s helping shift narratives and public opinion.

For too long, Western journalism has been complicit in or actively participated in recycling propaganda and erasing Palestinian narratives. I think there has been a growing distrust of mainstream media, and people are seeking knowledge.

Storytelling is our way of reclaiming truth.

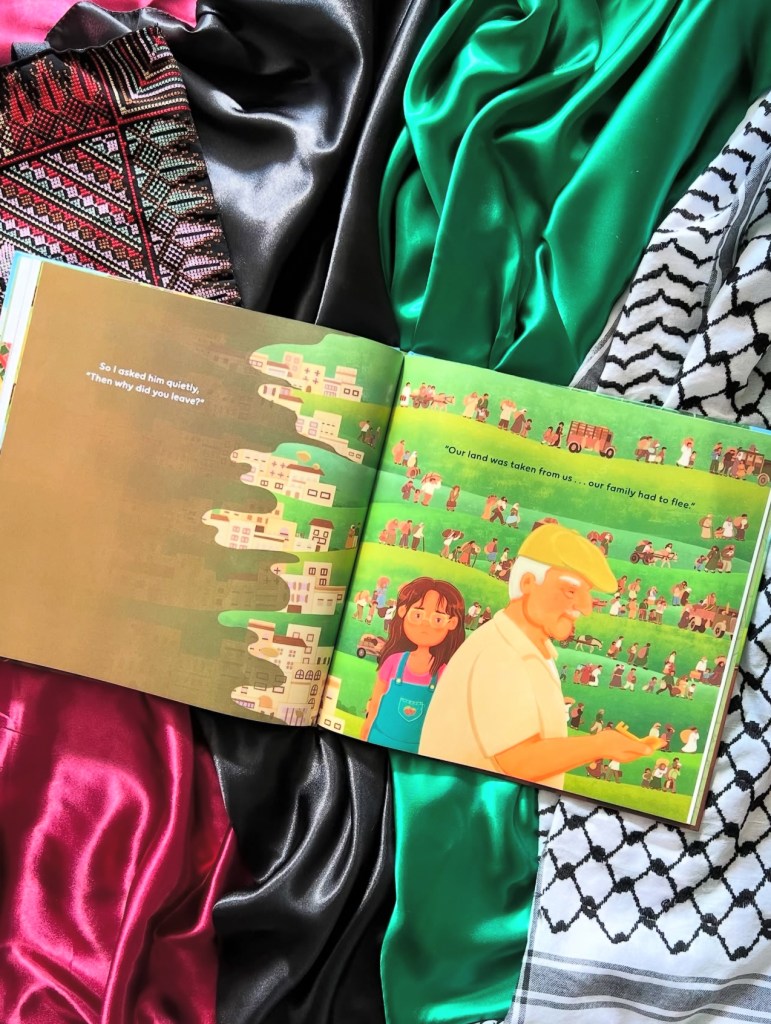

Congratulations on the recent publication of your children’s book, Everything Grows in Jiddo’s Garden! What was the inspiration behind it, and how did the story evolve creatively?

The idea came from an interview I did with my maternal grandparents in early 2022. I sat them down in front of a phone camera, with the intention of learning more about their childhoods.

In my twenties, as I started learning about Palestine and my family’s connection to it, I realised most of my questions for my grandfather had always been post-Nakba, about his life as a refugee and through displacement. I’d never asked about his actual childhood or learned much about my great-grandparents. I wanted to preserve those stories while I still could, so my children could one day hear them directly from their ancestors.

During the interview, my grandfather talked about his love of gardening, and although I grew up with him gardening, I never fully understood his connection to it. I used to think, “I don’t know why this old man is breaking his back doing this gardening when we can just go to the grocery store and buy whatever we need?” But then I learned that his father, my great-grandfather, had been a landscaper and gardener in Palestine before the Nakba, so before 1948. Gardening was not just a hobby; it was a heritage and a tradition he was carrying on.

Later in the same interview, my grandmother told me how they survived the Civil War in Jordan in the early 1970s, during a time known as ‘Black September’. She had two young children, my mother and her sibling, and they couldn’t leave their house without the fear of getting shot in the crossfire of the Civil War. How did they survive and sustain themselves during this time? She tells me that throughout their entire displacement experience, my grandfather kept the gardening tradition alive, wherever he went. So, in their home in Jordan, he sustained a garden protected by the four concrete walls of their home, and that was what they had lived off.

That completely reframed everything. Gardening was now more than ‘tradition’; it was a literal form of survival. It was the garden that had kept them alive.

At first, I didn’t know how to tell this story. I thought it might be a film or a novel. Then a friend of my husband’s suggested it could be a children’s book. As soon as he said it, I could visualise it: bright colours, simple rhymes, a story children could engage with.

I had a newborn and a three-year-old at the time, and I didn’t even know how to talk to my kids about Palestine. So I started doing some market research and realised most Palestinian children’s books were aimed at older readers, maybe ages 6–12. My kids couldn’t focus on those stories. But they could listen endlessly to rhyming books like Dr. Seuss. That’s when I understood I needed to write something rhythmic, colourful, and simple: a Palestinian story in a format even toddlers could connect with.

So, I sat down and wrote Everything Grows in Jiddo’s Garden in about twenty minutes. I pitched it to Interlink, the only Palestinian publishing agency in the U.S., and they immediately loved it. I also requested that Aya Ghanameh, a Palestinian illustrator whose work I admired, join the project, and Interlink made it happen.

This book became the first in the U.S. written by a Palestinian author, illustrated by a Palestinian artist, and published by a Palestinian press. That was deeply intentional.

When we launched it, we paired it with a fundraiser supporting farmers and seed protectors in Palestine. Every limited-edition box included Palestinian-made items: a keypin, keffiyeh notebook, colouring pages, stickers, olive oil and za’atar from Canaan Palestine, a child’s gardening shovel, and an embroidered gardening apron that was tatreezed by Palestinian women through Deerah in Jordan. Most importantly, each box contained heirloom seeds from the Palestine Heirloom Seed Library.

All profits, approximately $8,000, were allocated to support Palestinian farmers and seed preservation programs. These initiatives help protect native crops and offer stipends to people who grow and return Palestinian seeds, keeping our agricultural heritage alive despite the destruction of nurseries and seed banks by Israeli forces.

So, I wanted this book to be a community project that also gave back to its community. Every single hand that touched this project was a Palestinian hand. I hoped it would be an example that we could create beautiful things together.

Coming from generations of farmers and shepherds, I wanted to show that farming is at the heart of Palestinian identity, and that protecting our land is resistance, too.

Could you share a bit about your upcoming book, Displacement and the Palestinian American Story — what inspired it, and what themes does it explore?

Yes, it’s part of Penguin Random House’s ‘Race to the Truth’ series, set to release in fall 2026, and is aimed at a middle-school audience. The series helps correct the historical narratives American schools often distort or erase.

Each book is written from the perspective of a member of an underrepresented or marginalised community; for example, Colonisation and the Wampanoag Story tells the true history behind the first “Thanksgiving”, while others address slavery, Chinese exclusion, and the Mexican-American experience.

I was commissioned, alongside Alana Hadid, to write about the Palestinian American experience and displacement — and how the U.S. ‘participation’ in turning us into displaced people. It’s vital to teach children honest history.

You founded and lead Zaytoun Publicity, “where storytelling meets advocacy.” What challenges and achievements have defined your work as a Palestinian producer amplifying Indigenous voices?

I founded Zaytoun in 2021. I have a degree in journalism and around 14 years of experience in public relations and brand communications, but I have always previously worked for other agencies. In 2020, I was working at a boutique PR agency that I thought would be a long-term home.

I was often celebrated for my insights on diversity and inclusion, especially during the BLM movement. I helped craft statements, won awards, and led campaigns highlighting marginalised communities.

But when I was posting about Palestine in 2021, during the Sheikh Jarrah evictions, the agency asked me to remove the company’s name from my profiles so I wouldn’t be “associated” with them. My advocacy was celebrated until it was about Palestine.

That was my breaking point. I realised I couldn’t let anyone control my livelihood based on whether I spoke up for my people. So I left and founded Zaytoun Publicity.

My goal was to make media more equitable; to give space to BIPOC, queer, and Indigenous founders whose brands deserve visibility but often can’t afford expensive PR campaigns. There is a disparity in whose stories get to be told. The best stories are rarely the ones with the biggest budgets.

For three years, it was just me. Now it’s become a collaborative freelance network that supports Palestinian and social justice campaigns, including BDS initiatives. We’ve even hired people who lost jobs for speaking out on Palestine, including two recent hires who were fired and resigned after refusing to cancel my book event.

Zaytoun has become a truly wonderful and supportive agency that I am incredibly proud of and grateful to exist. We needed to show people that they would be supported when they stand strong in their morals.

The words ‘resilience and resistance’ appear in your profile, but these words are also circulating widely in both Western and Palestinian media and carry heavy connotations or projections with them. What do they mean to you?

Of the two, resilience is the one people are most comfortable with, but honestly, I’m exhausted by it. Palestinians are constantly praised for their resilience, but what that really means is we’ve been forced to survive. It shouldn’t be remarkable that we endure; we should be allowed to simply exist.

I have started to distance myself from it; I don’t want people to fetishise our resilience when they see Palestinians succeed.

Resistance was a harder concept for me to grasp growing up in the U.S. It was a very heavy word to fully understand. We’re taught to be docile and to see resistance to oppression or systemic injustice as unnecessary violence, and all of that hides the fact that oppression and systemic injustice are forms of violence themselves.

Resistance takes many forms: armed, literary, artistic, and educational. I’m just trying to do my part. I very much believe that the Palestinian diaspora has a responsibility to take part in the resistance. I always thought that because I was physically removed from the land, I didn’t have a part to play in fighting for it, or that I couldn’t; that whatever I did didn’t mean anything.

Over the last couple of decades, I’ve learned that I have a role too: to use my privilege and voice to reshape public understanding, challenge propaganda, and stand with my people in every way I can.

The ultimate goal is for the world to understand Palestinians as an Indigenous people. Conversations about Gaza or humanitarian aid must include the context of colonisation; otherwise, they miss the point.

You can send a million food trucks into Gaza to feed the people who are being forcibly starved. It will still not fix the root of the issue, which is that Palestine is a colonisation project on full display for the world to see. And if you can’t understand it, it’s going to happen to another place. It is already happening in other places around the world.

Colonisers don’t stop on their own; they must be stopped. Palestinians, both in the homeland and in the diaspora, are now working together more than ever to tell our stories and educate others. We know what needs to be taught and learned. We just have to be heard, too.

Jenan is a fierce advocate for the emancipation of all people who have suffered under oppression or systemic injustice. While she had never originally envisioned writing or publishing children’s books, she is much more than just a storyteller. From her grandfather’s garden to the growing success of Zaytoun, each story she writes or shares is a new seed promising to bloom into something more than just survival or existence.